Found places

"Place" is an important concept in our writing. Birthplace, current hometown, places we go back to again and again ... all of these define elements of our Being. True for White Rose friends as well.

I’m still processing many events and conversations from the Willi Graf Tagung eighteen days ago. As I process, I’ll document my thoughts in Substack posts, so you can follow along – and volunteer to work with us, or comment if something strikes your fancy.

One pre-conference goal was realized, namely, finding places for which we’ve searched since 1995. If you have read our newsletters or publications since the late 1990s, especially since 2002, you know that “place” is an important concept in our writing. Birthplace, current hometown, places we go back to again and again, favorite vacation spots, spaces for meditation and contemplation, places our dearest friends reside, burial plots – all of these define elements of our Being.

The first place “found” had bugged me for almost thirty years, I’m not a native Tölzer, but since the best shopping in the Kreis is in Bad Tölz, I’ve spent many hours lugging bags up and down its Marktstraβe over the past fifty years. I’ve also walked up (and down) Kalvarienberg dozens of times.

Therefore in 1995, I believed that finding the Borchers and Hartert homes would be among the easiest searches of that 3-1/2 month research trip. Hans Scholl had been clear in an interrogation: Am Kalvarienberg 1. One. Eins. Oans. No luck with either home – no address for Borchers’ house, but that was less important at the time.

In 2002, we searched again. This time, we were armed with Jürgen Wittenstein’s insistence that Harterts’ house was located at Am Kalvarienberg 1, at the very top of the hill next to the chapel. “Hartert’s house on the Kalvarienberg? It was (and is) the one at the very top, nr. One.” (Letter to me dated February 3, 1996.) – He repeated a vaguer version of this claim in his Shoah Foundation testimony, March 1997. His so-called “reconstructed diary” also states that Hans Scholl, and by implication he, had visited the Harterts at their home in Bad Tölz. Am Kalvarienberg 1, as Hans Scholl said. At the top of the hill, per Wittenstein. Interestingly, Wittenstein never mentioned the Borchers’ home.

In 2002, we started at the bottom of Kalvarienberg and walked the “Aufgang zum Kalvarienberg” path up to the Leonhardikapelle (Leonhard Chapel) and the Kreuzkirche, checking every house on one side going up. House numbers roughly (but only roughly) correspond to the stations of the cross along the way. As we expected to find House Number One at the very top, it confused us no end when the house numbers increased, corresponding to the stations. Walking down, we checked houses on the other side.

At the very bottom, we found House Number Two, with no “One” across the street. A friendly man stood in front of House Number Four, so we asked him. He had no idea.

Two possibilities crossed our minds. First, houses could have been renumbered since 1943. That happened often in postwar Germany. Or, where Kalvarienberg “ended” and a small alley to a larger street veered off to a sharp angle, that could have been where House Number One was located.

Over the years, I’ve obtained ever-older maps. Asked old-timers. Wrote Tölz city hall. Nothing helped. Wittenstein died insisting that Harterts had lived at Am Kalvarienberg 1, at the top of the hill. Since he married Hellmut Hartert’s sister Elisabeth Hartert after the war, we assumed that even if all else were lies, he had to have told the truth about that single item.

This year while shopping for walking shoes (Meindl!), a smaller carry-on (I love Toni Kirner Lederwaren), and an addition to my Tölzer wood carvings, plus eating Apfelstrudel as it is meant to be eaten – warm and with a hot vanilla sauce at Café Schuler – I saw the big blue I for information about halfway up Marktstraβe. Couldn’t hurt, I thought. So in I went and asked the very patient Birgit Groβ my Hartert-Borchers question.

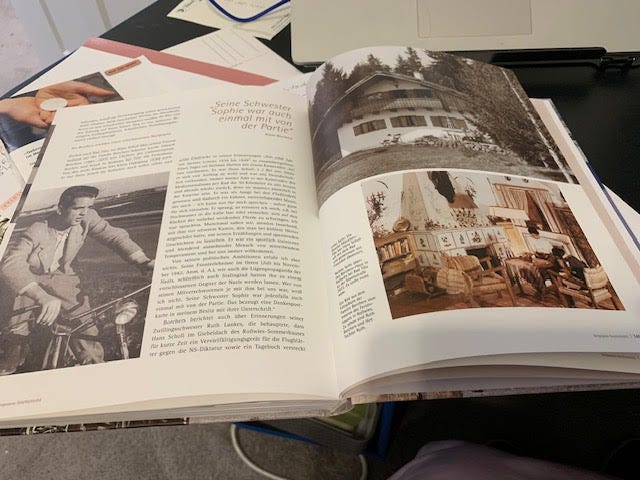

After a bit of chit-chat, she said she wondered if a book they stocked could possibly have that information. Bad Tölz: Rare Fotos, vergessene Geschichte(n) 1920-1950, by Christoph Schnitzer. Co-authors: Martin Hake, Sebastian Lindmeyr, Stadtarchiv Bad Tölz. Supported and published by Raiffeisenbank im Oberland eG and Stadt Bad Tölz. Martin Hake gets the credit for a great deal of the White Rose-Bad Tölz research.

Apparently by tracking the title to the house, Martin Hake was able to determine that the Hartert home in Bad Tölz had been purchased by Tölzer Baugeschäft Schneider and continues to serve as headquarters for that company. A quick Google search showed that to be “Aufgang zum Kalvarienberg 4.” Note that the house faces Maierbräugasteig – Aufgang zum Kalvarienberg is the steep path itself, which is not drivable except by horse-drawn cart on Leonharditag. When I took the picture, I made sure to get one with the company sign.

Hake also learned that the Borchers’ home was located in Roβwies, about 4 km from Tölz, a northern suburb in the countryside. Roβwies is a tiny hamlet, even smaller now than it was in 1942-1943, since the Borchers’ summer home has been demolished. Hake was able to get pictures of the house and family, together with Hans Scholl and perhaps Alexander Schmorell (we need someone to verify that it is Alexander in the photograph).

Those six pages are going in our database, as they add color and breath to White Rose friends. [Note to Schnitzer et al: If you reprint, recommend removing the positive comment about Wittenstein. He was not one of their group of friends, and his lack of familiarity with the Harterts’ (!) house raises even more questions. It’s one thing to get the house number wrong. It is quite another not to know it was the next-to-bottom house, not the one at the top of the hill!]

In addition to color commentary, the Hake-Schnitzer research explains another aspect of White Rose work that is being added to our Call for Papers. Borchers’ primary home was in Aachen and especially Hans Scholl corresponded with the Borchers siblings in Aachen. Schmorells also had relatives in Aachen. Add in the chocolate factory connection mentioned in the Protokolle (also Aachen), and the network expands. A network we know absolutely nothing about.

Finding the Harterts’ home ended a great shopping day in Tölz. Priceless.

Next excursion took me to Starnberg. Lilo Fürst-Ramdohr wrote in her memoirs that she met up with Arvid and Mildred Harnack at the “Bridge Museum,” later corrected to “British Museum,” code name for clandestine meetings with others from the Harnack-Schulze-Boysen group, aka Rote Kapelle.

Thanks to Lilo’s grandson Domenic Saller, I knew before leaving Gettysburg that the British Museum was also known as the Kornmann Villa. Domenic had found the address in his grandmother’s documents. Egon Kornmann owned the villa and was friend of the Harnack family. Kornmann also associated with Arnold Sommerfeld, whom I write about in White Rose History Volume II. Sommerfeld was professor emeritus of theoretical physics (and mathematics) in Munich.

Mister Siri was able to map out a pleasant journey from Bad Heilbrunn to that address in Starnberg. But as I drove up the increasingly narrow street high above Starnbergersee, the homes grew increasingly tonier, with gates and security systems galore.

From those trips in 1995 and 2002, I knew better than to take a picture willy-nilly, without consequences. (In Krauchenwies, when photographing the manor house where Sophie Scholl carried out her Reich Labor Service, we were compelled to hand over a roll of 35mm film and delete all video taken that day. We had taken pictures of the current manor house, where nobility still lives, while Sophie had worked at the rundown manor house up the road. It was fine to photograph the dilapidated structure.)

I took my pictures – through the gate – and then sat in the car and waited. A few minutes later, neighbor across the street appeared and wrote down license plate number. I waited still. It did not take long until the homeowner drove up to the gate. I got out of my car and approached her. She was very nice, confirmed that they had bought the home from the Kornmanns many years before. She knew nothing of its connection to Rote Kapelle, the Harnacks, or Arnold Sommerfeld. I gave her a business card and asked her please to contact me should she stumble across new information.

I tell you these gory details in case you decide to make a trip to Germany ‘on the trail of the White Rose,’ with or without the benefit of our travel guide. As noted in that guide, exercise caution when taking photos of homes, especially expensive homes. Even Google Maps does not provide street view images of the Kornmann villa. So I am not posting my photograph here either.

It was just a sense of success to see it in person after 20+ years! It hit home in a new way that the Harnacks and Kornmanns and Schulze-Boysens were part of the privileged upper class in Germany. They could have easily kept their cushy jobs and pretty houses and expensive lifestyle, if they had just kept their mouths shut and done what The Man said.

But they did not. Justice, freedom, honor, not just for Germans but for all, mattered more. They were willing to walk away from wealth for the courage of their convictions. House with a view or Hitler’s meat hook? And they chose the meat hook.

After finding the Kornmann villa, I drove back to Bad Heilbrunn through Pöcking and Poβenhofen, Manfred Eickemeyer’s “place.” He attended boarding school near Passau, but especially Pöcking remained home for him. Christmas 1942 was spent with his sister in Pöcking, before returning to his studio in Munich. His renewed association with Hans Scholl and new friendship with Wilhelm Geyer in January 1943 would change Eickemeyer’s life, just as he changed theirs with his horror stories about German doings in Cracow.

I did not find Eickemeyer’s home in Pöcking, nor the homes of his mother and siblings who lived there. No exact address given in his Protokolle. But Pöcking is close to Bad Heilbrunn, so I’ll be back.

Over the course of the two weeks, I also got great leads on two locations that have increased in importance for me. First, Herta Probst’s postwar address in Bad Heilbrunn. The story behind those three months will open up a new, poignant thread for the Probst family, if it leads where I think it will. It clearly meant a lot to her.

And less pleasant, but perhaps of Greater Global White Rose Significance, I have a lead on the Gestapo version of the Protokolle. The documents that Christiane Moll uncovered in former East Berlin in 1989 consist of the prosecutors’ files. Wittenstein mentioned having used the Gestapo’s version of those files. We know from Susanne Hirzel’s memoir that there were five bookcases full of documents, five bookcases filled with binders.

Which makes sense, since one Gestapo report noted that they believed approximately 180 people were involved with White Rose resistance. Logical conclusion would be that they had interviewed close to 180 “suspects” in the matter. My best efforts come up with around 90, and that number includes non-suspects.

Fully half the story is not contained in the 5000 pages of Protokolle in the Bundesarchiv. (Care to hazard a guess how many pages would be in the binders contained in five full bookcases? 5000 pages = 10 reams of paper, or one box, if you buy office supplies.)

This “thing I still don’t know” segues nicely into the sole disappointment related to place from this trip. Namely, I may have to temporarily give up on finding the Drei Burschen Hütte in Lenggries where Willi Graf retreated the week before his arrest. It was a ski hut well-known to him and his friends (not Scholls), and it was the place he went, hoping to meet up with Johannes Maassen, hoping for an introduction to Pater Delp and the circle of active resistance around that man.

Over the years, I have asked a friend in Lenggries, I have written to the town of Lenggries, I have written to the Alpenverein, I have gotten a friend who’s a member of the Alpenverein intrigued and researching (thank you, Cornelia Küffner!). All to no avail. I asked Christoph Schnitzer – he had carried out similar enquiries, with the same results.

Until more documents are found, perhaps from some of Willi Graf’s non-Munich friends?, it looks like this ski hut will remain a mystery. A pity.

Found places… just a few, but the White Rose story grows with each new place.

© 2023 Denise Elaine Heap. Please contact us for permission to quote.