Freedom

In 1968, Wilhelm Geyer stated of the White Rose students, "Freedom was the alpha and omega for this group." On this Juneteenth, let's consider why freedom matters. To all of us.

Having grown up in Houston, Juneteenth has been part of my Being for a very long time. Especially once I started researching my great-grandfather Sachs’ life and found that he was one of the only “white” businessmen to join Houston’s Juneteenth parade in 1899. Made the Houston Post!

Freedom also played a central role in White Rose thinking. Following are direct quotes from things they read and commented on, things they wrote or said… Some wanted freedom for all, others wanted freedom for Germans, while a few focused solely on personal freedoms. These distinctions should not be overlooked.

But for today, let’s simply celebrate their passion for freedom and make it part of our lives as well.

February 12, 1933. Willi Graf and his best friend Robert occupied their Sunday afternoon by reading words written by Johannes Maassen. “Censorship of the press is as common these days as fresh bread, because German freedom has been sold on the open market. …

“We seek a national honor that is miles removed from the wretched clay of excess and the gutter. This gutter is fast becoming the norm in daily life and opposes everything that does not worship the current government. We seek the complete existence of justice, the basis of the true state. We seek a gateway for the freedom of the Volk.”

November 23, 1936. Christoph Probst wrote his stepmother Elise that he had been chosen to play the role of a “freedom fighter” in a play written by Walter Erich Schäfer about the October 18, 1813 battle in Leipzig.

January 12, 1937. Christoph Probst wrote his stepmother that he longed for the “freedom of the mountains.” I started not to include this one, because it seemed too trivial. And yet, it is not.

February 11, 1937. In another letter to his stepmother, Christoph Probst wrote, “It is nearly Easter, and with it, a little freedom. I think about it so gladly. I so long for freedom. I see all the gates through which one could break out, and they are locked.”

September 2-11, 1939. Designated as Party Day of Freedom. Ironic, since Hitler had long before planned his invasion of Poland for that week.

January 8, 1941. Letter from Sophie Scholl to Fritz Hartnagel. “I came home happier after such walks. I should make the time or freedom to go on them more often.”

February 10, 1941. Letter from Hans Scholl to his parents. “Today I learned that there is no chance we will get an exemption. This was only to be expected. It means I've got another two months of so-called freedom. Sometimes I feel like losing my temper, but today I don't mind too much about these things, especially as the sun is shining on the just and the unjust alike. That, at least, will shine forever. I shall manage to preserve my inner freedom, even in the army. Werner will find it harder in the beginning.”

February 24, 1941. Letter from Hans Scholl to Rose Nägele. “It won't be long before my little taste of freedom comes to an end. I'm always on the move these days. It's too tempting to drop everything and play hooky. I've regained my conception of what freedom is. I tread the high roads once more and leave all else to the Almighty, or my sudden impulses, or I set myself a destination and get there if I feel like it.”

March 13, 1941. Letter from Hans Scholl to his parents. “Many thanks for Mother's letters and packages. I would like to sneak off to the mountains with Werner for a day or two before he joins the Prussians. Anyway, I would strongly advise him to put his freedom in the right perspective by doing such a thing. Man lives by memories as well as by ideas.”

Leaflet I, around June 1, 1942. Written by Hans Scholl. “If the German nation is so corrupt and decadent in its innermost being that it is willing to surrender the greatest possession a man can own, a possession that elevates mankind above all other creatures, namely free will – if it is willing to surrender this without so much as raising a hand, rashly trusting a questionable lawful order of history; if it surrenders the freedom of mankind to intrude upon the wheel of history and subjugate it to his own rational decision; if Germans are so devoid of individuality that they have become an unthinking and cowardly mob – then, yes then they deserve their destruction.”

Leaflet III, around June 30, 1942. Hans Scholl penned this section. “Every individual human being has the right to a useful and just State that guarantees the freedom of the individual as well as the common good. For mankind must be able to attain his natural goal – his temporal happiness – in self-reliance and autonomy. This pursuit of happiness should take place free and unencumbered in association and collaboration with the national community, in accordance with God’s will.” (Alexander Schmorell wrote the second half of this leaflet.)

July 27, 1942. Christoph Probst to his younger half-brother Dieter Sasse. “For a person who lives intellectually and spiritually, this accursed monastic seclusion can have a deepening effect, because after the fact, he sees things previously taken for granted with a new awareness and finds that his feelings for life’s freedoms have been intensified.”

October 19, 1942. Letter from Carl Muth to Hans Scholl. “I am happy that you are able to give yourself the feeling of freedom for the time being.”

Leaflet V, around January 13, 1943. “Freedom of speech, freedom of religion, the protection of the individual citizen from the caprice of criminal, violent States – these are the bases of the new Europe.”

Leaflet VII, unpublished, around January 31, 1943. Written by Christoph Probst. “Today, all of Germany is encircled just as Stalingrad was. All Germans shall be sacrificed to the emissaries of hate and extermination. Sacrificed to him who tormented the Jews, eradicated half of the Poles, and who wishes to destroy Russia. Sacrificed to him who took from you freedom, peace, domestic happiness, hope, and gaiety, and gave you inflationary money.

“That shall not, that may not come to pass! Hitler and his regime must fall so that Germany may live. Make up your minds: Stalingrad and destruction, or Tripoli and a future of hope. And when you have decided, act.”

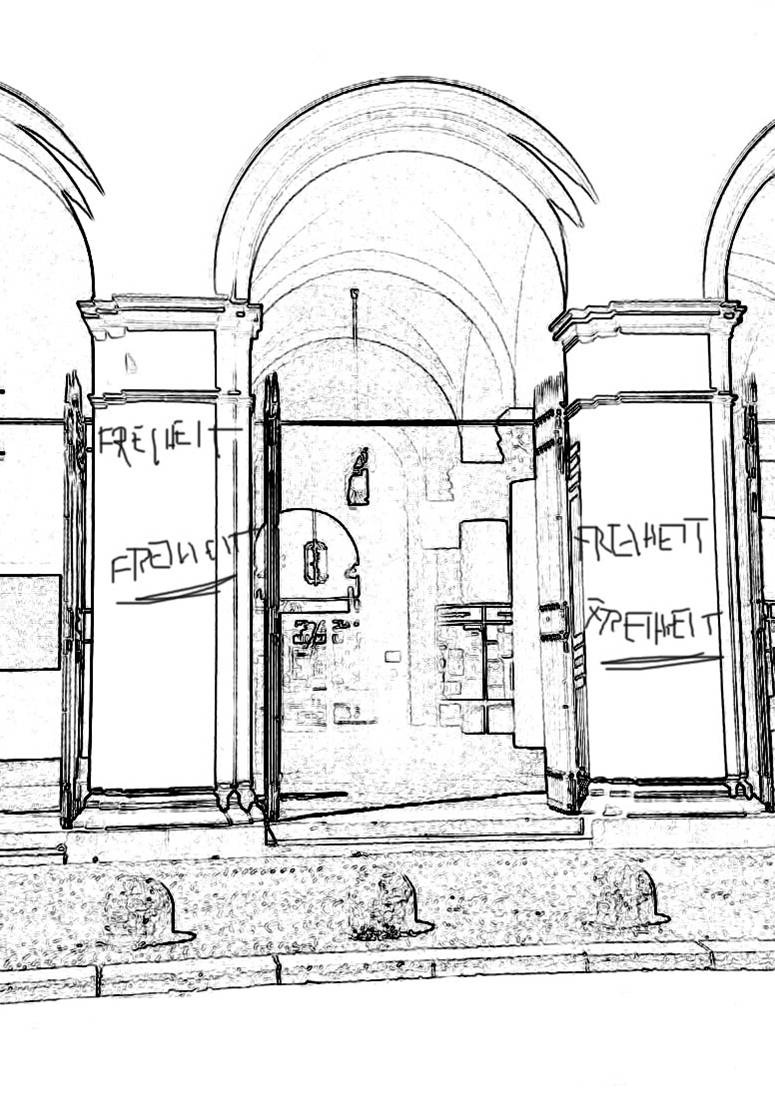

February 3, 1943. Accompanied by both Willi Graf and Alexander Schmorell, Hans Scholl painted the word FREEDOM four times on the walls of the university, to the right and left of the entrance.

Leaflet VI, around February 11, 1943. Written by Prof. Dr. Kurt Huber. “The day of reckoning has come, the reckoning of our German youth with the most abominable tyranny that our nation has ever endured. In the name of all the German youth, we demand that Adolf Hitler’s government return to us our personal freedom, the most valuable possession a German owns. He has cheated us of it in a most contemptible manner. …

“For us now there is but one watchword: Fight against the Party! Get out of the Party organizations in which they wish to keep us politically muzzled! Get out of the lecture halls of the SS-Noncom-or-Major-Generals and the Party sycophants! This has to do with genuine scholarship and true freedom of thought! No threats can dismay us, not even the closing of our colleges.

“This is a battle that we all must fight for our future, our freedom and honor in a political system that is conscious of its moral responsibility.

“Freedom and honor! For ten long years, Hitler and his associates have abused, stomped, and twisted these two glorious German words till they are loathsome. Only dilettantes are capable of doing this, dilettantes who cast the highest values of a nation before swine. Over the last ten years, they have more than shown us what freedom and honor means to them – they have destroyed all material and intellectual freedom and all moral substance in the German people. The terrible blood bath that they have caused in all of Europe in the name of the freedom and honor of the German people – a blood bath that they cause anew every day – has opened the eyes of even the stupidest German.

“The German name will be forever defamed if German youth does not finally arise, avenge, and atone, if he does not shatter his tormentor and raise up a new intellectual Europe. Students! The German nation looks to us! In 1943, they expect from us the breaking of the National Socialist terror through the power of the spirit, just as in 1813 the Napoleonic [terror] was broken. Beresina and Stalingrad are going up in flames in the East, and the dead of Stalingrad beseech us: “Courage, my people! The beacons are burning!” Our nation is awakening against the enslavement of Europe by National Socialism, in a new pious revival of freedom and honor!”

February 18, 1943. Gisela Schertling’s initial interrogation. Emphases in original. “Both Scholls are very religious [klerikal, not gläubig or fromm] and frequently told me that our current theory of life needs renewal, and that Christian movements needed to be propagated. Scholl primarily stressed that another era must come in which there was more freedom in the fields of art and literature.

“Both of them were primarily critical of the fact that the Führer allows the church so little freedom and that he does not permit the cultural movements that emanate from it [the church] to grow to maturity. They also often said that they believed that democracy must once again come [to Germany].

“I argued these political matters vehemently with Scholl, because I was largely of the opposite point of view.”

February 18, 1943. Sophie Scholl’s initial interrogation. “I would like to add as an additional and (in the end) the most important reason for my antipathy to the movement: I perceive the intellectual freedom of people to be limited in such a manner as contradicts everything inside of me. In summary, I would like to state that I personally would like to have nothing to do with National Socialism.”

Ferbuary 22, 1943. From report of Hans Scholl’s execution. “The condemned was calm and collected. His last words were ‘Long live freedom.’

“Time elapsed between transfer to the executioner and the fall of the blade: 7 seconds.”

February 27, 1943. Prof. Dr. Kurt Huber’s initial interrogation. “I also found myself in the most difficult political – but also moral – conflict of my life and thought with the development of the political situation since the end of the French campaign, along with the (in my opinion) increasing threats of intellectual-spiritual freedom of the individual and of my research, teaching, and politically successful activity, which followed the (in my opinion) drift to the left in German national policy. I have complete sympathy for a strong policy in the East. However, I could not inwardly justify the ever-increasing numbers of blood sacrifices in the East. [Emphasis in original] …

“I firmly decided that I would break my silence. In one way or another, I would announce – not to the general public, but to the decision-makers in the Party – what the people and the student body and the faculty think about this measure taken against personal freedom and honor.”

March 2, 1943. Margarete Hirzel’s letter about her son Hans Hirzel. “We raised our older children with great independence and freedom. Therefore we do not know when his political activity began. It probably began last year in Munich.”

March 8, 1943. Falk Harnack interrogation, describing the contentious discussion the week of February 9, 1943. “When I had read the leaflet, another man arrived, who was introduced as a professor. After I read the leaflet, I stated my opinion particularly about the point where it reads: ‘Germany of the future can only be a federalist [förderalistische] state.’ I alleged that on the contrary, Germany must remain unified, because historical development pointed to large countries. I reacted undecidedly to Scholl and Schmorell‟s ideas. I tried to stir them up to tell me what form of government they envisioned. They said it was their opinion that the new government had to have 2 or 3 parties, one of which must be an opposition party. These parties would make up the new government. Further, they envisioned a group of united federalist [förderative] states, and absolute economic freedom. …

“He [Hans Scholl] then posed the question about freedom of religion, a subject we agreed about. This discussion also contained questions about education.”

March 8, 1943. Susanne Hirzel’s political Curriculum Vitae. “I was supposed to place the letters in mailboxes without being noticed. Therefore I concluded that what I was doing had to be dangerous, but I did not think about it any closer. Hans [Hirzel] told me we would not hurt anything. I thought it was possible that something in the letters could have something to do with domestic policies, e.g., educational matters, or about some church matter or another (although I know of nothing in particular), or that there should be more artistic freedom. …

“During my time with Jungmädel, my parents gave me complete freedom in my work, although I was often stretched beyond my limits and I was urgently needed at home.”

March 8, 1943. Prof. Dr. Kurt Huber’s political statement. “During the interrogation, I stated that the primary motivation for my energetic action was my growing concern with regards to the increasingly leftward drift of the government. Central to this concern is the increasing limitation of the personal freedom of the individual: Freedom of thought, freedom of conscience, freedom to act. One must recognize that the danger and force [Not und Wucht] of our mortal combat against Russian Bolshevism requires the strongest unyielding concentration of all our energy. It is a whole other matter whether this concentration ensues from the full dedication of the personal freedom of every individual, or whether it comes from the external impetus of fundamental reeducation. [Language is convoluted in original.] That reeducation may not have the Bolshevization of the German nation and people as its goal, but it is in fact the end result. I believe the latter is the case. …

“The Germanic ‘Führertum’ is built on the idea of inviolable personal freedom of every member of the nation. It is not the will of the Führer that is law. Rather, the will of the Führer is an expression of the law. The will of the Führer is subject to law by the representation of the people. He can be elected, and he can be removed from office. The German authoritarian nation is not an authoritarian ‘Machtstaat,’ which is what the current German government has become. Our government can no longer be reconciled to the demands of personal freedom.

“And this is where my inner conflict arises. …

“Enough of the brief description of the basis for my ideas. For me, the demands for freedom of thought and freedom of conscience flow out of that basis, and precisely for the authoritarian nation [‘Führerstaat’] of German persuasion. Now to the political: The Germanic Führer is indeed open to criticism within legal bounds. [But] the authoritarian ‘Machtstaat’ says that all critique of national leadership is an illegal activity. It completely prohibits freedom of speech, freedom of assembly, and freedom of the press. This development too cannot be reconciled with the moral demands of self-determination.

“I will only mention the religious freedom of conscience briefly here. There is no doubt that in his speech in Potsdam, the Führer initially agreed to this. There is equally no doubt that in the current ‘Machtstaat,’ the open and secret battle against Christendom has assumed forms that cannot be differentiated from the methods used under Russian Bolshevism.

“I must now go into a little more detail regarding the growing prohibition of scientific freedom of thought. …

“Freedom and truth must once again become the hallmarks of the German press. I have already emphasized the demand for freedom of speech (even if not completely uncensored). But also objective news reporting must once again return to a simple, factual, and as true as possible representation of the facts, instead of the exaggerated propaganda currently known. It must do this if it wishes to reach free, responsible people and not sink to the level of a [Illegible]. …

“I would like to summarize the above thoughts by once again emphasizing: I did not wish to bring about a revolution through my deeds. Rather, the opposite is true. I wish for the current regime to return to a nationalistic and moderately socialistic interpretation of the authoritarian principle [‘Führerprinzip’], one that unconditionally demands freedom and independence of the individual.

“I do not in any way wish for a return to the ideology of the Western democracies and parliamentary governments that we survived [Weimar]. But I ask and plead with the Führer to build a dam [einen Damm entgegenzusetzen] to prevent the threatening Bolshevization of the German people. The solution in short is: Turn away from the authoritarian ‘Machtstaat’ to a contemporary fulfillment of the true Germanic ‘Führertum,’ and turn away from the threatening mob nation to a collectively constructed nation of the people [‘Volksstaat’]. …

“I wish to assert and I have sufficiently emphasized that my fundamental political opinions that I was able to present briefly here are substantially and fundamentally in agreement with those of the current regime. …

“If I could personally make but one request of the Führer, it would be to spare my poor family [meine arme Familie] and at the last hour to grant me a personal audience.”

Note: Machtstaat means authoritarian nation. Huber’s semantics split hairs in trying to define the difference between a Führerstaat (which he approved of) and a Machtstaat, which he did not. Both are authoritarian regimes led by a strong “Führer.”

[The entire six-page political dissertation can be read in the volume of Kurt Huber’s Protokolle: NJ1704 Vols. 2, 7; and, NJ1704 Vols. 10, 13, 20. The third volume labeled Huber and Harnack is primarily Falk Harnack.]

March 9, 1943. Letter from Margarete Hirzel to the Gestapo about her daughter Susanne Hirzel. As far as I am aware, she was the only person worried about this particular sort of freedom. “Political attitudes: Susanne Hirzel does not have any particularly affirmative or particularly negative attitudes to the State and to the Party. Unlike the older generation, she does not have the luxury of comparison. She only knows the multi-party State and the imperial Reich from history books. She can theoretically evaluate the great achievements of social contentment, of currency freedom [Währungsfreiheit], or of market regulation, because she has learned about them. But she knows nothing of the prior misery.”

March 17, 1943 (estimate, undated). Excerpt of letter from Professor Alfred Saal to the Gestapo on behalf of Susanne Hirzel. “With regards to previous discussions with her, I do not believe that she was fundamentally opposed to the National Socialist State. She merely was concerned that it could later limit the freedom of religion. I have had no such conversations with her in recent months. When total war [totaler Krieg] was declared, she said that she completely agreed with it and that she would gladly make herself available, because it was now less important that one should make music.

“Once before she told me that she hated all coercion. That is why she did not wish to join the [NS] student union.”

March 27, 1943. Katharina Schüddekopf Curriculum Vitae. “For me, studying at the university does not mean the accumulation of historical knowledge; rather, it means life. As it has always been, [education] is learning about that which is independent and free, with as little outside influence of time and space and the wisdom of mankind and books as possible. The freedom of German universities has always been treasured in every European nation. It is the symbol of the most prominent feature of Germans in general. The battle for the very last freedom – whether the battle is waged with the sword of the spirit or the sword of iron – has made us into a tragically heroic people. We know no peace, no self-contentment. We know only the battle for an idea and the unwavering faith in victory.”

March 29, 1943. Gisela Schertling interrogation. “Their [Hans and Sophie Scholl’s] critique of the National Socialist state was always negative. They thought English democracy was the proper example. They particularly criticized the limiting of personal freedom. They thought they could bring about a transition to a new government by convincing individuals to revolt [auflehnen] against the current regime. The figure of speech ― revolt against the current regime – was only used once on the occasion of a meeting. But on that occasion, the participants did not go into greater detail as to how they imagined the revolution against the State.”

March 31, 1943. Gisela Schertling interrogation. “During the first meeting, they primarily talked about politics. The second time, they did not. I noticed that Hans Scholl and Probst‘s father-in-law [Harald Dohrn] primarily led the discussion. From Dohrn’s conversation, I could tell that he was basically opposed to the National Socialist state. He championed the Catholic point of view very fanatically and was critical of the fact that the Church’s freedom had been so limited by National Socialism.”

April 1, 1943. Gisela Schertling interrogation. “I must admit that under the political influence of Hans Scholl, my political attitude gradually became shaky. It got to the point that I began to doubt National Socialism. In particular, I began to share Hans Scholl’s view that National Socialism limits personal freedom too much. He was additionally able to convince me that the rights of the churches had been limited too much by National Socialism, and that they had unjustly been cut off. He was also finally able to make me doubt our leadership. However, I never participated in Scholl’s treasonous criticism or that of his circle in any way.”

April 5, 1943. Wilhelm Geyer’s initial interrogation. “I always tried to persuade Hans Scholl to give up his fealty to England [Englandshörigkeit], to point him to another way of thinking. In contrast, Scholl longed for the moment when the English would march into Germany and restore order. However, I will not deny that I see limits on personal freedom under the current regime in many things, and that I expressed this opinion openly during these conversations. I could not see that anyone contradicted me in this point. In any case, I did not try to persuade or incite the remaining participants (of this meeting) to undertake treasonous activities or to become active opponents of the current regime or to overthrow it. Willy Graf and I were the ones who primarily tried to keep the conversation grounded in reality and reject everything that was excessive [alles Überschwengliche].”

April 8, 1943. From the indictment for eleven of the White Rose friends, regarding distribution of the leaflets. “However, their distribution was to be limited to Southern Germany, because it alone was accessible for thoughts of an established, freedom-oriented form of government.”

April 16, 1943. Interrogation of Prof. Dr. Kurt Huber. “I will admit that the National Socialist government perhaps views the problem of community and individual correctly. However, in practical matters in many instances that leadership is questionable because of its breaking [Brechung, also aberration] of personal freedom. For example, the laws regarding treason forbid every – and that means every – public criticism of alleged grievances in public life.”

September 21, 1968. Wilhelm Geyer to Inge Aicher-Scholl, recording his memories of those days in Munich. “The week before [the first graffiti campaign], Alex had asked me how to make a template. Freedom was the alpha and omega for this group. Their sense of human dignity had been wounded.”

I resisted the urge to editorialize as I quoted their words.

On this day when news of emancipation, of freedom, finally made its way to Texas, and slaves held there were unshackled, we too should think what it means to be free. The sacrifice of freedom for security rarely ends well.

How do the words of these friends – both students and their mentors – affect you? Does anything ring especially true

?