Happy anniversary to us!, belatedly

July 1994, I had no idea I was embarking on a journey that would tackle historical revisionism and counterfactual versions of White Rose resistance. As hard as it's been, I wouldn't change a thing.

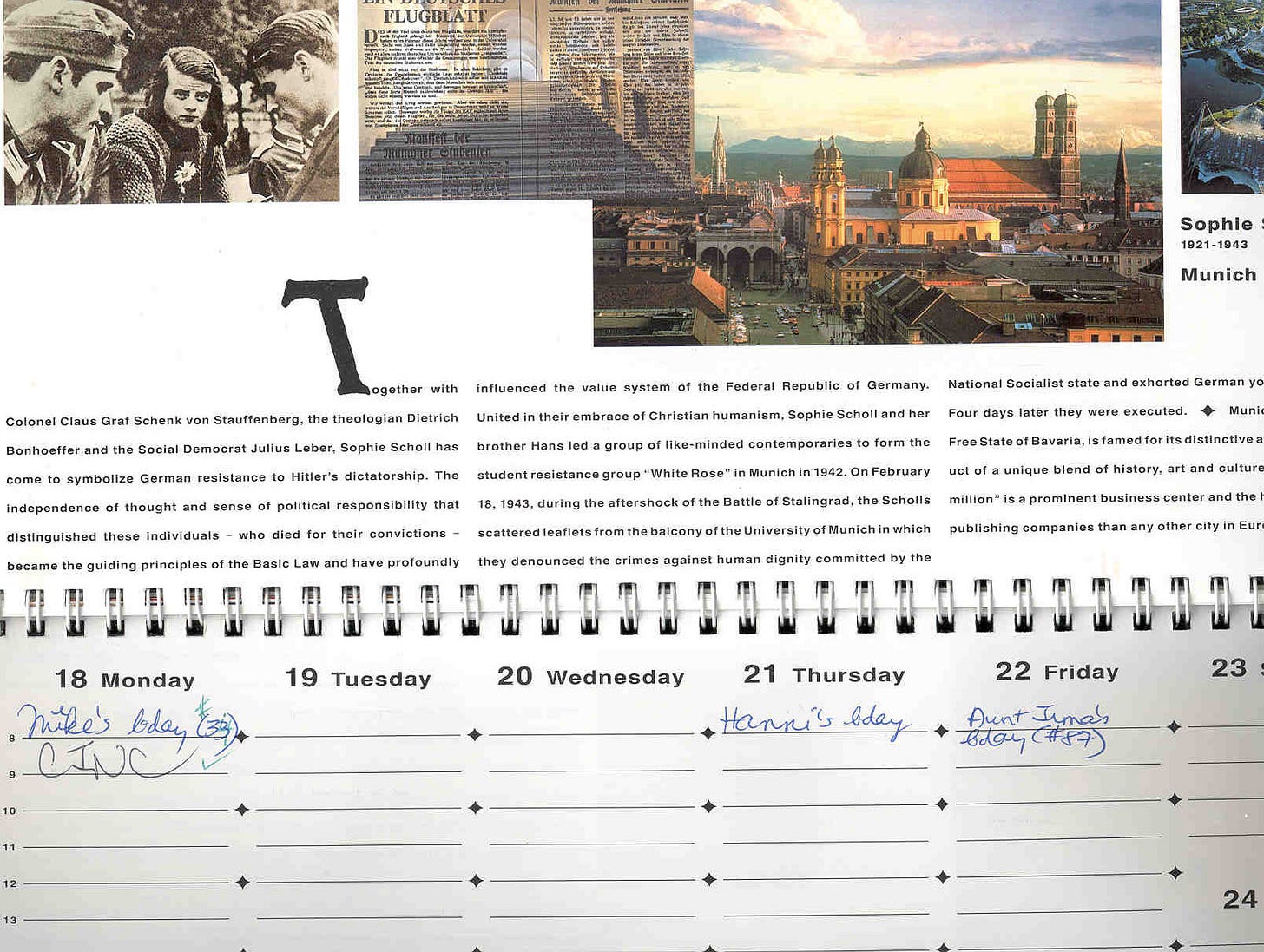

July 18, 1994, I first learned about White Rose resistance thanks to the calendar handed out to members of the German-American Chamber of Commerce. Since I had taken German since seventh grade at Spring Branch Junior High School (thank you, Frau Pieratt and Frl. Grooters for your inspired teaching!), and neither teachers nor professors had mentioned White Rose resistance, I assumed they must have been Communists.

For the next six months, I labored on a book about the White Rose. First draft, completed before the 3-1/2 month research trip to Germany in 1995 “to wrap up loose ends,” is now almost humorous in retrospect. Scholl-centric, with everyone perfect little angels sporting highly polished haloes, the first draft sounds a lot like most White Rose “scholarship” even in 2023.

That first draft would be irrevocably annihilated during the 3-1/2 months of talking with White Rose family members, touching Alex’s samovar, reading the original letters Wilhelm Geyer wrote from prison, walking the streets of Blumberg, sitting with Prof. Dr. Inge Jens as she described the horrific state of White Rose scholarship, questioning Fritz and Elisabeth Hartnagel in their home about the Scholl-centric nature of the legend, passing muster with Anneliese Knoop-Graf, hearing Gustel Saur’s stories of her (and her brothers’) association with the Scholl family, taking copious notes as Dr. Silvester Lechner spoke, and much, much more.

Even research in dusty archives yielded nuggets that changed, well, everything. Once people learned I wasn’t telling the same old same-old story, their demeanor immediately transformed from eye-rolling to enthusiasm. They’d dig out obscure newspaper articles, find photographs, and relate anecdotes they’d kept bottled up for decades. I’ll never forget the woman at the city archives in Ulm who had been classmate of Sophie Scholl and knew her as a real-life person. Her stories were about a flesh-and-blood human, not about a bust at Valhalla.

This journey, now almost thirty years in the making, has taken unexpected twists and turns. After Betsy Colquitt reviewed the fourth or fifth draft of our histories, she remarked that I should count on pushback because the real story was so different from anything on the market. She recommended footnoting as has never been footnoted, couched in more reserved terminology. Her comment prompted us to found Exclamation! Publishers in 2002, so we could publish primary source materials in English translation. If anyone questioned a fact or a footnote, we could point them to the source document.

Three years later, while ensuring that everything from the Protokolle was in our Microsoft Access database, I once again reviewed the infamous backsides of some of those documents.

Back story: In May 2002, I was beyond annoyed with the people at the Bundesarchiv in Berlin. In January, I’d asked about ordering a complete set of Protokolle. They quoted price, including shipping for 5000 pages. When we compared airfare, shipping cost was nearly as expensive as flights. We therefore placed the order, with scheduled date for pickup in Berlin in May 2002. We also were able to arrange interviews with people we had missed in 1995: Susanne Zeller-Hirzel, Herta and Micha Probst, Lilo Fürst-Ramdohr and her grandson Domenic Saller, along with return visits to White Rose families who by now felt like our own.

Arrived for that Bundesarchiv pickup four months later, and they had not even started the copying process, despite firm pickup date. I asked to speak to the manager, and to my surprise, the Director of the Bundesarchiv in Berlin appeared. Following a few minutes of mutual appraisal of the person across the table, the floods turned when I told him I was only having to get the documents from Berlin because Inge Aicher-Scholl had instructed Franz Josef Müller not to let me read the copies at the Weiβe-Rose-Stiftung in Munich. Müller had obediently advised me of Inge’s decision. I was persona non grata, for reasons she never explained and I never understood.

The minute the Bundesarchiv director knew that Müller and Aicher-Scholl were essentially antagonistic to my work, and that I had doubts about Wittenstein, that minute was magic. It opened a dam of information, something completely unexpected when I woke up that May morning. I was able to obtain – legally – copies of the Protokolle for Franz Josef Müller and the Hirzel siblings, gesperrt or blocked by those individuals.

The director also honored my request for “every scrap of paper in the archives related to White Rose resistance, no matter how small” along with “please, ensure that includes backsides of all documents!” Because the initial set of documents I had received in 1995 had had backsides missing, some transcripts were not complete.

Best of all, he provided me with the option to receive all 5000+ pages on microfilm instead of printed. Even a cursory run-through of the microfilm showed me backsides of documents.

Now, back to 2005 and my review to ensure everything was in the database: Some of those backsides were for persons unrelated to White Rose. Others who had resisted and had been interrogated by the Gestapo… the backsides of White Rose documents revealed tiny, tiny snippets of their stories. Woefully incomplete. But starting points. I was seeing their names solely because Germany was running out of paper in 1943 and 1944, and Gestapo agents had to recycle old files when typing up new interrogations.

Suddenly, although my histories were still important, the scope of what we had undertaken exploded. I was heartened by Hans Forster’s proclamation that “if anyone can find the truth about the White Rose, it’s you,” but remembering that he had also bemoaned the fact that I was working on “yet another White Rose book, when there are so many” had always bugged me a little. Seeing the backsides of documents explained his reasoning.

And thus, Center for White Rose Studies was born. We chartered in Pennsylvania in 2005, with 501(c)(3) obtained a few years later.

There are many anniversaries related to this work – some legal, some sentimental. But that July 1994 day when a terrible Houston landlord refused to repair air conditioning quickly, forcing me downtown to sit in a cool library and read inaccurate books about the White Rose? That anniversary sticks with me.

Postscript regarding teachers: My very first German teacher, Frau Marie Louise Pieratt nee von Gronau taught all of us in junior high school German class about German resistance. Her father, Wolfgang von Gronau, was a famous German aviator, feted not only in Europe, but in the USA as well. See New York Times for articles about his accomplishments.

He was also part of the July 20, 1944 resistance. Frau Pieratt showed us grainy B&W movies from the 1950s about her dad. She also told us how much she hated him, growing up as a teenager in Germany. He would not allow her to join Bund deutscher Mädel, making her an outcast among her friends. She also remembered clandestine meetings in their home, placing pillows over telephones (bugs) and using blackout curtains during the day. She hated him. Until she became an adult and understood his reasons.

Harriet Dishman nee Grooters continued our superlative education in high school. We did not learn about German history from her, but she was a “mean” teacher in that she truly taught us the language and challenged us to think and write in it. While we were in high school! I placed out of two years, four semesters, of university German thanks to her. And thanks to her, was confident talking to Germans, even as my language skills were improving (i.e., before they were good).

Note for the record: She was anything but a “mean” teacher. Beloved by us all, many of us are still friends with her mumble mumble years later. But she was strict when it came to grammar, pronunciation, vocabulary, and other things “popular” language teachers tend to skip over. She should write a book about “how to teach German!”

This spate of great teachers continued at TCU. Irmtraud Feigs, Olan Hankins… Irmtraud told us what it was like growing up as a young child in postwar Germany. Olan taught us to read between the lines when analyzing literature.

Pieratt, Dishman, Feigs, Hankins - I learned from them not to accept anything at face value, but to ask questions until I could think of no more questions, and not to accept pat answers. So much of my White Rose work is owing to what I learned from these four remarkable teachers.

Postscript regarding our work: This post from February 24, 2023 is reminder of ways you can join our work. We still need scholars, researchers, admins, interns, Advisory Board members for CWRS, a GOOD Board of Directors for CWRS, database experts, writers… I am moved down to the bottom of my toes by people who responded five months ago and who are moving us forward. Future posts will focus on them and what they are doing.

But there is room for you. If you subscribe to our commitment to the ethics of Holocaust scholarship, if you are sick of historical revisionism and counterfactual versions of German resistance, if you are ready to ask hard questions and take the pushback that comes from establishment “scholarship,” please please, contact me! There is plenty of room at our table.

© 2023 Denise Heap. Please contact us for permission to quote.