Karma for Nazis, or, cigarettes made in Dresden

History is never a direct trail of logical events.

Between 2016 and 2019, I spent several months working in Dresden. Despite going back and forth to Germany from 1973 to present, and despite a two-week trip behind the Iron Curtain in 1987 visiting Weimar, Leipzig, Magdeburg, and former East Berlin, I had never been to Dresden.

There’s a building off the beaten path in Dresden that stands out for its unique architecture. You would swear you’re seeing a mosque, complete with exquisite minarets. In the old days, Dresdners nicknamed it the Tabakmoschee, the tobacco mosque. That term is no longer in vogue, since it is not a mosque and never has been.

It’s called the Yenidze building. Yes, with a Y. After an Ottoman town of the same name.

You see, Hugo Zietz together with his young architect Martin Hammitzsch needed to circumvent Dresden’s zoning laws. Zietz’s cigarette business had been established in 1886. By the beginning of the 20th century, Zietz needed a larger factory. But Dresden would not permit a factory that looked like a factory to be built where Zietz wanted.

Enter Hammitzsch, then a twentysomething up-and-coming architect. The two men devised a plan to build a factory that paid homage to the Turkish roots of Zietz’s Orientalische Tabak- und Zigarettenfabrik Yenidze, or Yenidze Oriental Tobacco and Cigarette Factory. They made it look like a mosque from the Yenidze area. The minarets disguise chimneys, since City Hall prohibited chimneys that close to the Old City.

Zietz even had steam engines built to light up the inside of the beautiful dome, projecting the words Salem Aleikum for all to see. The most popular brand? Salem Gold, unrelated to the US brand of a similar name.

There are many ironies built into the above narrative. Hugo Zietz was Jewish and traded freely and without rancor with his Muslim counterparts in the Ottoman Empire. Martin Hammitzsch would marry Adolf Hitler’s older half-sister Angela in 1936. After World War I, Angela ran a dormitory for Jewish university students in Vienna, protecting her boarders from antisemitic mobs that tried to assault them. She was a large woman and did not hesitate to use her size to advantage as she beat away “Aryan” hoodlums.

After Angela married Hammitzsch, her on-again, off-again relationship with Germany’s Chancellor was strained. Hitler did not like Martin. But after 1941, Angela sold out to her famous half-brother and eventually worked directly for him. After the war, she even defended Adolf. (Hammitzsch suicided at war’s end.)

Hugo Zietz did not live to see the Third Reich. In 1924, he sold Yenidze to Reemtsma, a tobacco conglomerate. Zietz died in 1927, and his wife and entire family emigrated to Switzerland and the USA.

Reemtsma paid off Hermann Göring – extortion, to stop a frivolous lawsuit brought against Reemtsma by the SA (Sturmabteilung), because right up until 1935, Reemtsma kept their Jewish C-Suite and shareholders, over Nazi protests. Reemtsma’s Jewish executives emigrated in late 1934 and 1935, with help from Reemtsma management.

Once Reemtsma was Judenfrei, management negotiated with the NSDAP. All soldiers received cigarettes for free as part of their monthly pay. Reemtsma now had almost 2/3 market share, as they became the official cigarette provider for the German military.

Here is where “karma for Nazis” kicks in:

In 1929, while Reemtsma maintained its Jewish staff and enjoyed harassment and disfavor from Nazis-on-the-rise, an upstart cigarette manufacturer appeared in Dresden: Cigarettenfabrik Dressler KG. Established in August 1929 by Arthur Dressler, this company adopted a multitude of brands, including Sturm, Trommler [drummer for the military], D3 [Third Reich], Alarm, Neue Front [New Front, Nazi organization].

Dressler wanted to sell cigarettes, but he faced fierce competition from what had been Yenidze, and most certainly from Reemtsma. More than wanting to sell cigarettes, Dressler wanted to ingratiate himself with the NSDAP, the wave of the future. He wished to get in on the ground floor.

He therefore struck a deal with the Sturmabteilung, the SA. The SA would “suggest” to its members that they only smoke Dressler brands. Dressler agreed that he would develop brands that would specifically appeal to SA members. And they would split the profits, with the SA guaranteed a minimum payout of 250,000 Marks or $2 million annually.

Hence, the SA attacks on Reemtsma, with its Jewish shareholders and executives, and the SA lawsuits against Reemtsma, forcing them to pay extortion to Göring. They were protecting their bottom line.

Everything went swimmingly until June 1934. Dressler’s high-ranking friends inside the SA were murdered during the Röhm Putsch, also known as the Night of the Long Knives. Overnight, Dressler’s business model tanked. Reemtsma recognized the opportunity to knock out its major competitor – and took it. Dressler’s company went bankrupt less than a year later.

David Schnur, the Jewish executive at Reemtsma whom the Nazis hated most, emigrated to France with his family shortly after the Röhm Putsch. In 1939, they would be among the last group to make it safely to the United States, where they became citizens. The New York Times carried his obituary on March 17, 1948. The obituary was entitled, “David Schnur, Made Foreign Cigarettes.” The irony there? The SA had accused Reemtsma of making “Jewish cigarettes.”

History is never a direct trail of logical events.

Yenidze Tobacco and Cigarette Factory survived the carpet bombing of February 1945 nearly intact. Only one wing saw any significant damage.

But Dresden was in the Soviet zone after the war. The beautiful building was used simply as a warehouse, war damage not repaired, for the duration of the existence of the German Democratic Republic, the DDR. Only after the fall of the Wall would the “Tobacco Mosque” be restored to its original glory – by an Israeli businessman.

The saga of the Zietz family, who dreamed Yenidze into being, was not quite finished. In the 1950s, our Internal Revenue Service sued Willy Zietz, the sole surviving heir, for an exorbitant amount of back taxes. We know quite a bit about the fortunes of the Zietz family post-Dresden from this lawsuit. Hugo Zietz received approximately $4 million in 1924 dollars, or $74 million today, for his business.

After Hugo’s death, his widow and their two sons relocated to Switzerland. They lived a lavish lifestyle. Despite substantial ongoing income, every year they whittled away their inheritance by a few hundred thousand here or there. The two sons appear to have been the biggest drain on the family’s income.

By 1959, less than $1 million was left, $10 million in today’s currency. And the IRS said Willy owed them $250,000 of that.

On May 31, 1960, a New York judge ruled in favor of Willy Zietz. No tax was due on the inheritance from his father.

But the biggest irony of all? This battle over who got the cigarette concession, first from the SA, then for the entire military, was waged in a regime that officially banned smoking! One of Bishop Melle’s selling points as he traveled the USA raising money from American Methodists for the NSDAP involved Adolf Hitler’s “character,” since Hitler was a vegetarian who did not drink alcoholic beverages, did not smoke, and was “chaste.”

To pull all the strands of this crazy square inch of the tapestry together:

A Jewish tobacco and cigarette manufacturer built a factory designed to look like a mosque to sell Turkish cigarettes. His architect would later marry the half-sister of Adolf Hitler. The Jewish cigarette czar sold his company to another company that employed a Jewish executive to run their cigarette division. Because of the Jewish executive, the SA hassled the second company, extorting it. Yet another would-be cigarette czar founded a company specifically to sell to the SA and became wildly successful. Until the Röhm Putsch, when his benefactors were murdered by Adolf Hitler. Which enabled the second cigarette company to step in and take over the cigarette concession to the German military, but only after all their Jewish executives emigrated from Germany. And after the fall of the Wall, an Israeli restored the factory that was designed to look like a mosque.

And this took place in a country that supposedly banned smoking, even while providing cigarettes as part of monthly pay to its soldiers.

Got it?

If so, please explain it to me!

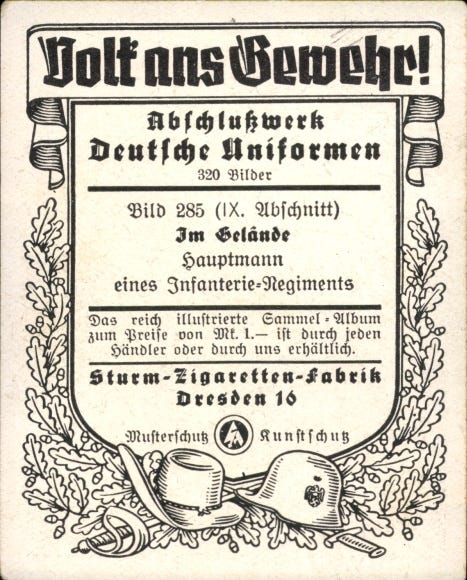

You should recognize the two Sturm cigarette images from today’s “podcast” or audio book segment. This rabbit hole came about when I was looking for a generic picture of a German army Captain during WW2 and found this. When I saw “Dresden” as location for Dressler, I wondered if it had been a subsidiary of Yenidze, and if Yenidze had been Aryanized and given to Dressler.

What I discovered was infinitely more fascinating! Hope you think so too.

I also took pictures inside Yenidze, because that building housed the offices I was working out of. On the ground floor, the current owners have wonderful photographs of Yenidze and the Zietz family in their heyday. Unfortunately, those photos don’t transfer well to Substack (hard to read).

Oh, and Zietz had an eye for location. Yenidze is directly on the Elbe River, so access to barges. And it’s a short walk - maybe half a mile? - from Dresden’s main train station, and less than a mile from downtown Dresden with its banks and businesses, and Old City.

© 2024 Denise Elaine Heap. Please contact us for permission to quote. To order digital version of White Rose History, Volume II, click here. Digital version of White Rose History, Volume I is available here.

Why This Matters is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber. - All subscription funds are deposited directly to the account of Center for White Rose Studies, a 501(c )(3) nonprofit. Ask your tax accountant if your subscription is tax deductible.

Thank you so much you for your article Denise. I'm happy someone has covered this very interesting story. Willy Zietz was my father. My mother worked in Switzerland as his personal secretary until his death. My mother eventually married someone else and we emigrated to the United States in 1969.

Hugo Zietz is my great-uncle. His brother, Emil Zietz, immigrated to the U.S. in the 1890s, and settled in Denver, Colorado. My birth father, Emil Zietz (same name) is one of his children. Though I never met my birth father, as he passed before I was 18, I have met other members of the family in the U.S. I live in California. I would LOVE to see any and all photos of my family. Please contact me at Louise Z: z7414207@gmail.com. Thanks so much!