Susanne Hirzel: The other side of words

Words matter. We must use words deliberately, consciously. In contrast to Hermann Krings' clear text, Susanne Hirzel's words muddy the waters. See how that makes a difference in the record.

When I first read Susanne Zeller-Hirzel’s memoirs, entitled Vom Ja zum Nein, I was surprised by how much I liked the book. I knew that she and her brother Hans Hirzel had publicly recanted their White Rose work, embracing far right-wing, anti-Muslim, anti-immigrant politics. Germany for Germans! That was the battle cry they had adopted.

This paradigm shift had taken place in 1994, when Hans Hirzel ran for the German presidency on the Republikaner platform. And it had been a big deal, with the Weiβe-Rose Stiftung terminating their participation, and the Weisse-Rose-Institut e.V. not accepting them in their ranks. People who had known the siblings for years were speechless at the sea change in their political attitudes.

I expected Susanne’s book to reflect that ideological transformation. After all, her memoirs were published in 1998, four years after their public repudiation of the principles they had embraced during the Shoah. Or at least, principles they seemed to have embraced during the Shoah.

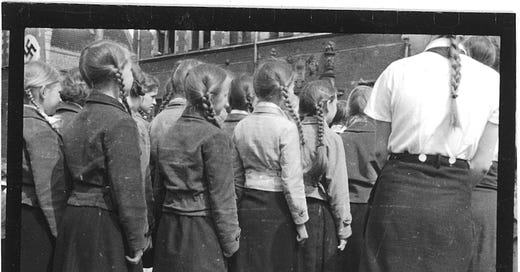

Instead, I found a reasoned, logical treatise on life in Germany during the Third Reich, and Susanne’s moving from happy Jungmädel leader to fearfully courageous distributor of White Rose leaflets in Stuttgart. She recounted in her memoirs the treasonous conversations she had had with Pastor Rudi Daur, as well as with fellow students in Stuttgart. [Our review can be found here.]

Several passages leapt off the page at me, almost Krings-like in their specificity and unambiguity. In their seeming specificity and unambiguity.

Chapter 10 of our White Rose History, Volume I begins as follows:

That summer of 1937, not all dangerous words saved lives. Antisemitic expressions gained momentum, becoming part of the vernacular. Slurs once articulated only by those readily identifiable as National Socialists were now an element of everyday speech. If you wished to vex an acquaintance, you would likely call him a “half-Jew,” regardless of his ethnicity.

Other insults included ‘Don’t be in such a Jewish hurry’ or ‘Whaddya think this is, a Jewish school?’ These invectives had grown ever more dangerous in that they were deemed acceptable, pervasive evidence of emergent racism. Once integrated into language, such abuse can be hopeless – if not impossible – to purge.

Consider our own experience, almost forty years [2002] after the civil rights movement caused us to think about our racist history. We still hear phrases like “Are you trying to Jew me down?” Or, “That’s awfully white of you.” If we find it hard to rid our language of offensive idioms, it was doubly difficult in 1937, when the words were considered politically correct.

I properly cited my paraphrase of Zeller-Hirzel’s book, footnoted as “Susanne Hirzel, Vom Ja Zum Nein, p. 60.”

I was also pleasantly surprised to find that Zeller-Hirzel covered her personal recollections of Kristallnacht in Ulm, as well as the discussions around the dinner table in the Hirzel home about the events of November 9, 1938. If you have followed our work for very long, you will know that Kristallnacht remains a gaping hole in White Rose history, with no one willing to talk about it. Inge Aicher-Scholl has apparently heavily censored all correspondence and diary entries from both Hans and Sophie Scholl for the period from November 9, 1938 + three weeks, as well as the six-week period from April-June 1939 when the Scholls took possession of the apartment on Münsterplatz (presumably because of its former Jewish inhabitants).

But it’s not just Scholl. Even the usually transparent Anneliese Knoop-Graf provided no evidence of Willi’s doings or thoughts on Kristallnacht, much less her own. The 890-page volume of letters by Christoph Probst and Alexander Schmorell, edited by Christiane Moll, jumps from March 21, 1938 directly to Summer 1939 for Alex, and from May 3, 1938 to October 13, 1938 for Christl. The first published letter post-Kristallnacht from Christoph Probst to his Jewish stepmother is dated April 19, 1940. Search all you want. I have yet to find letters or diary entries or memoirs that address where people were, what they were thinking, what happened to their friends, on Kristallnacht. White Rose to date has been the story of “German resistance,” yet missing some of the most critical events of the Third Reich.

Therefore it was a breath of fresh air to read Zeller-Hirzel’s text, recounting her difficult memories. From Chapter 13 of White Rose History, Volume I:

Susanne’s vulnerability as she writes of those days endeared her to me long before I met her face to face. No holds barred, she admits to anger, shame, oppression, as the dominant sensations she cannot forget. Anger that anyone could treat a house of worship with so much disrespect – ‘Jews today, and us tomorrow?’ Shame that her cowardice got the best of her, and she was afraid to seek out the very Jewish friends she had treasured, to inquire how they had fared. She remembers how embarrassed she was, how great her fear at facing people she held dear (and she has never quite gotten past her “lack of courage”). Oppression, knowing that nothing could ever be the same, that Germany had crossed a line from which there was no retreat, that things would soon be worse than anyone could dream possible.

“And all this could happen because we had a government we could not get rid of, that had no opposition. A government that refused entry to foreigners and the news they would bring with them. A government that developed its own propaganda. A government that bludgeoned and terrified its own people with terror, legal uncertainty, and suppression of freedom of speech. That even made its people indifferent, apathetic because they were unconscious.”

She buried herself in music, refusing to read the newspapers or do anything that would expose her to the horrors that seemed to mount with each new day. For her in that day, at that time, reality was more than she could bear.

Again, properly footnoted: “Susanne Hirzel, Vom Ja Zum Nein, pp. 80-82.”

Finally, in Chapter 9 of White Rose History Volume I, I quoted a passage from Otl Aicher’s memoirs in conjunction with Zeller-Hirzel’s description of a beloved biology teacher named “Mr. Waaser.” Zeller-Hirzel usually told wonderful stories about the teachers she admired, but when it came to Mr. Waaser, she did not say much. Whereas Otl Aicher vividly recalled the reasons he venerated that man.

When Mr. Waaser therefore made no secret of his affiliation with that society [anthroposophy], he made himself vulnerable to detention and deportation to a concentration camp. Susanne observes that her biology teacher had to watch what he said, aware that the slightest unacceptable comment could result in his denunciation by a student.

Otl Aicher declares in his memoirs that someone should erect a monument to Mr. Waaser. He offers a depiction of his physical attributes, “short gray hair, walked slightly stooped over – he protected himself with the friendliness and the smile of a Chinese man.”

To illustrate Mr. Waaser’s significance in their lives, Otl cites a story he attributed to Mark Twain, about a writer who died and went to heaven. Ecstatic at finding himself among literary greats, this writer asks God who the best writer of all was.

The Almighty showed him a forgotten poem, found in the desk of an unimportant teacher in a village school. This, said God, was the greatest writer, and no one knew him. To Otl Aicher, Mr. Waaser was that writer, even if he had never written a poem.

“Only someone who has lived in dark times can know what it means – what it perhaps means to someone personally – when a biology teacher stands up in front of a classroom, gives a brief introduction to the fundamentals of the natural sciences, and then says, ‘Biological substance is worthless as a subject matter. If I were to hold a National Socialist in one hand, and in the other a pile of feces, the two would be – strictly biologically – one and the same.’”

So wrote Otl Aicher in 1985 as he contemplated the educators who had profoundly impacted his life. Someone should erect a monument to Mr. Waaser.

Both were properly cited. “Susanne Hirzel, Vom Ja Zum Nein, p. 90.” And, “Aicher, p. 27.”

In 2002, before completing White Rose Histories Volumes I and II, we took another research trip to Germany, three weeks talking to people and working in the Bundesarchiv in Berlin. Susanne Zeller-Hirzel was among the people we spoke with, spending an entire afternoon with her in her home. Asked her questions about her memoirs, things I had not understood. It was an amiable conversation.

When we left her home, there was a huge cloud of puzzlement hanging over our heads. How could this be the same woman who wrote such hate-filled speech against Muslims and immigrants? She did not seem to recant her words, “And all this could happen because we had a government we could not get rid of, that had no opposition. A government that refused entry to foreigners and the news they would bring with them. …”

As a result, we decided to keep these and other quotes in our Histories. I had worried that if she were going to repudiate her own memoirs, it could be risky to quote her.

It has long been our practice to send a copy of our work to people we interviewed or corresponded with extensively. Half an hour in the archives did not merit a free copy of the book. Those people received the sections where they were quoted.

But Erich and Hertha Schmorell, Lilo Ramdohr, the Probsts, the Geyers, Inge Jens, Anneliese Knoop-Graf, Traute Page, Hartnagels – and Susanne Zeller-Hirzel – those people received a full print version of the Histories. We wanted them to have the opportunity to make corrections or adjust our perspective if necessary. (All of them had received transcripts of our interviews, so they knew we would quote them correctly long before they saw the Histories.) With Zeller-Hirzel, the quotes came straight from a published memoir, so there should be no misunderstanding.

And now, I learned my second priceless lesson about “the value of specificity, the weight of unambiguous language,” as I wrote on Monday about Hermann Krings’ priceless lesson.

Because for all of Zeller-Hirzel’s book learning – and she was indeed a brilliant woman! – she did not share Krings’ commitment to those philological or academic values. What she wrote was not necessarily what she meant. On December 16, 2002, I received a harsh letter from her. In her view, I had no right to write about White Rose or any subject related to the Shoah, because I did not live during those days.

“This appears… [ellipses in original] to be a very nasty and unnecessary supposition that shows that you did not experience the conditions and the atmosphere of those days.” Ironically, in her memoirs she wrote about Germany during her father’s era.

Zeller-Hirzel forwarded copies of her December 16, 2002 letter to everyone she knew, including the Hartnagels, Dr. Armin Ziegler, her brother, the Scholls (of course), just to name a few. She tried to destroy our work before it even got off the ground.

Working backwards: Zeller-Hirzel refused to accept Aicher’s anecdote about Mr. Waaser. She insisted that Otl did not know Waaser, with the direct implication being, ‘as well as she did.’ She claimed, “The story in this form is atypical of Mr. Waaser and should not have been published. It defames a dead person.” It defames Mr. Waaser only if a person disagrees with Waaser’s conclusion. Otl Aicher – and I – would like to see a monument erected in his memory, because we agreed with him, as most anti-Nazis would. Defamation?

Next, she was absolutely furious about my using her words about Kristallnacht. By December 2002, she was placing the blame for Kristallnacht on Grynszpan, not on NSDAP thugs.

Zeller-Hirzel tried (and failed) to walk a fine line here. Her anti-Muslim rhetoric was couched in “philo-Semitic” terms, as if hatred for Muslims was something the Jewish community in Germany would want. At precisely the same time that she espoused anti-Muslim ideology, Ignatz Bubis – then the president of the Central Council of Jews in Germany – was fighting for rights of all minorities in Germany, including both the Jewish and the Muslim communities. When he died on August 13, 1999, the Muslim community along with the Jewish community mourned his passing, reflecting on his fight on their behalf. I remember how AOL’s message boards were flooded with German-Muslim sympathy posts after Bubis’ death. It demonstrated the world as it should be, as it could be.

Whatever Zeller-Hirzel thought about her anti-Muslim sentiments in Germany being compatible with her mock philo-Semitism, she was wrong.

Another gripe she had with my quoting her short section on Kristallnacht centered on my description of the brutality of that night and the subsequent vicious treatment of Jewish citizens of Ulm. Along with quoting her memories, I had used personal accounts from the Jewish community in Ulm, documented in Zeugnisse zur Geschichte der Juden in Ulm, published by Ulm’s Stadtarchiv in 1991. A lengthy review of that book is on our Book Review site.

The few examples used in our White Rose History Volume I highlighted the visibility of the arrests, beatings, and even deaths of prominent Ulmer who happened to be Jewish. I especially focused on the families that lived in the same apartment building as the Scholls. Many of the Jewish neighbors and former colleagues and fellow students who interfaced with Scholls and the rest of the “White Rose” circle in Ulm fared badly during Kristallnacht, losing family members to Riga or Dachau, or later to Auschwitz, if not being murdered themselves.

I was angry when I wrote that chapter of White Rose History Volume I, because I understood that that gaping hole hides important information that would allow us to better track the development of Hirzels, Scholls, Guter, Müller, and the rest, permitting them to have reinvented themselves with false stories of “Luise Nathan” and knocking on the Guggenheimers’ door, events that did not happen, “memories” not generated until after the war. Apparently, Susanne Hirzel’s ‘transparency’ only went so far. She proved unwilling to face those events, except in the most superficial manner, with shallow words.

Finally, I had given her the benefit of the doubt and had paraphrased – not quoted – her Kristallnacht statement about now-Jews-then-us. The words in quotation marks were the only ones actually quoted. The rest was paraphrased.

Because she had written, “Our family was moved by an additional concern: The synagogue was a church. Therefore, we knew it was possible that they would torch our church!”

The synagogue was not a church. It was indeed a house of worship, a house of assembly, a house of prayer. But it was not a church. It was not a Kirche.

Believe it or not, she threatened to sue me for having paraphrased her words instead of quoting them. That threat of lawsuit? The Acme anvil dropped. I knew then beyond all doubt how critical Hermann Krings’ viewpoint was, is, forever will be. Words matter. If a person embraces far right-wing politics and writes that a synagogue is a church… Words matter.

Which brings us to the last point. What Susanne Zeller-Hirzel wrote on page 60 of her memoirs was true. Calling someone a “half-Jew” as insult, or stating “Don’t be in such a Jewish hurry” or “Whaddya think this is, a Jewish school?” – those words destroyed. Those words were real. Those words harpooned the lives of Jewish business people, doctors, writers, teachers, students. Those words eventually enabled mass graves in Riga, eventually became gas chambers, eventually dehumanized not only Jewish Germans, but Jehovah’s Witnesses, Roma-Sinti, socialists, Communists, any group that Hitler arbitrarily decided he did not like.

And yet, on December 16, 2002, she now wrote me – with CC to the White Rose world:

“Sorry, you unfortunately do not understand our sense of humor. Your moralizing statement is therefore embarrassing. These were not invectives.”

Here is the exact quote from her book. Apologies in advance to readers who do not speak German, but this point – how a person who went to jail in 1943 fighting against a far-right regime, who wrote a brutally honest memoir about that fight, and who now aligns herself with the far-right Republikaner who have adopted much of Hitler’s platform – is too important for translation or paraphrase.

“So beleidigende Worte wie ‘Halbjude’ oder ‘Vierteljude’ wurden allmählich benutzt, ohne daβ man sich der Diskrimierung bewusst war, nur weil man täglich solche Worte durch die Partei hörte. Im persönlichen Verkehr jedoch, in unserem Umkreis, auch in unserer Schule hörte ich nie eine abträgliche Bemerkung. Redensarten: ‘Nur keine jüdische Hast’ oder ‘Hier geht’s ja zu wie in einer Judenschule’ zeigen selbstverständliche Vertrautheit.”

It is difficult to understand how a “beleidigendes Wort” cannot be considered an invective!

Had I asserted that she used those invectives, I could understand her antagonism. Had I asserted that I quoted what she wrote, instead of simply using the material paraphrased as basis for a general observation, I could understand her annoyance. When the second edition of the Histories is released in 2024 or 2025, I will find another source for that exact same claim.

Parenthetically: She had also made an observation in her memoirs that surprised me, knowing her political leanings. And it was an observation I had found both funny and astute. Zeller-Hirzel pointed out that Germans would say, “If only the Führer knew!,” while simultaneously saying, “Führer, wir danken Dir.” This was from page 82 of Vom Ja zum Nein, in the context of her Kristallnacht narrative on pages 80-82.

That December 2002 letter exploded all over the place about my praise for her statement. Directly contradicting herself, she said that Hitler did NOT know, referred me to Henry Picker’s Table Talk “proving” that Hitler did not know, and said that I had taken this quote out of context, pointing me to page 118 of her book, although her own discussion was clearly on pages 80-82, as footnoted. [Note that Picker was a very high-placed Nazi, working directly as senior executive in NSDAP headquarters. If she had approvingly cited his book in her memoirs as she did in her December 2002 letter, I’d have stayed away from her completely.]

Two-part conclusion of this post that became longer than intended:

First, words matter. Hermann Krings’ trustworthiness, using words deliberately, consciously – that is the way history must be written. If a scholar cannot rely on beleidigende Worte (“insulting words”) as synonym for invective, or conclusions remaining the same from 1998 to 2002, then the words are useless.

I am honestly at a loss as to how to treat Zeller-Hirzel’s memoirs in the second edition of the Histories. If you have suggestions, please post them in comments. This discussion should be out in the open.

Second, as I wrote last Friday:

Scholarship is not a popularity contest. It is getting your hands dirty in stubborn archives. It is wrestling with seemingly contradictory facts. It is puzzling out dates, reading bad handwriting. It is figuring out whether a document is real, forged, or altered. It is not accepting the easy story, but looking for reality.

Scholarship is hard work.

There were mixed results from Susanne Zeller-Hirzel’s December 16, 2002 letter as it made its way across Germany and into the German press.

On the one hand, some people used her attacks as basis to belittle me personally. I won’t mention those people by name here. Refuse to give them air. Just know there are about ten people whose work I do not trust, because they used Zeller-Hirzel’s letter as weapon. As very public weapon.

There were others who read her letter and were as flabbergasted as I. They knew her book, they knew what she had written. They knew I had quoted her correctly. They could not understand how the blazes she went from White Rose, to reasonably logical non-Nazi memoirs in 1998, to… to what? To a screed that belied any sense of decency, that accepted Henry Picker as source, that attacked me for quoting her correctly. More importantly, that suggested – no, emphatically stated – that someone who did not live those years could not write about them.

I will give them air. Thank you, Dr. Armin Ziegler, for standing up to her, responding to her letter with CC to me, defending me and my work in those newspapers that would not print the truth. Thank you, Michael Kaufmann, for understanding the source. Thank you, Erich and Hertha Schmorell, Herta and Micha Probst, Hermann & Martin & Elisabeth & Wilhelm Geyer, Lilo!, Inge Jens, Elisabeth Hartnagel, Hubert Furtwängler, Traute Page, for not wavering; I miss you and your dependable support. Your partnership in our Histories and in our continued research has meant the world to me. Thank you, Nigel and Domenic, for next-gen support!

Words. Matter. Truth. Matters.

In a world of Susanne Hirzels, be Hermann Krings.

Words do indeed matter, even (or perhaps especially) when they come back to bite us.