The elections of 1930-1933

They could not have imagined that such hard choices would be required of them. They certainly could not have known what was yet to come.

Over the past few months, there has been much ink spilled over the similarities between the election of November 1932 — followed by Hindenburg’s appointment of Adolf Hitler as Chancellor on January 31, 1933 — and our presidential election scehduled for November 5, 2024.

There are indeed many uncomfortable similarities, but the most profound discomfort comes from a careful reading of events during the Weimar Republic, preceding the November 1932 election. Hitler’s strategy did not appear unbirthed in 1932. Plans to overthrow the legitimate democratic government had been in the works since before Hitler’s association with the NSDAP. His addition to the party amplified the brutality that had always been below the surface.

Hitler understood when to use and when to restrain violence for political benefit. He also introduced theater to German politics - staging, microphones (Hitler loved microphones), parades, torchlight processions, rallies. Big rallies.

Below, I summarize the events of November 8, 1923 (date of the putsch attempt) through March 5, 1933 (date of the last free election in Germany until after the war). It is my sincere hope that this post gives you insight into the similarities and differences between these elections.

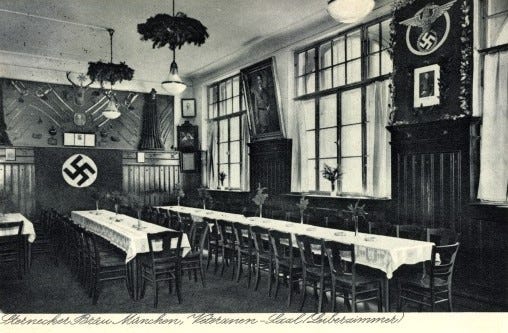

On November 8, 1923, Adolf Hitler – along with trusted comrades from the National Socialist Party in Munich – attempted a violent overthrow of the German government. Supported by brown-clad Storm Troopers, and accompanied by the much-respected General Erich Ludendorff (a famous World War I hero), Hitler marched into a Munich beer hall where Bavarian officials and important businessmen were assembled. He declared the formation of a provisional national government under the control of the National Socialist Party.

The regular police thwarted the Nazis’ attempt. At the end of the day, three police and sixteen Nazis were dead. Hitler escaped when his bodyguard shielded him and took several bullets. Hitler escaped in the middle of the volley and hid out in the attic of his good friends, the Hanfstängls, until he was arrested.

Even this setback played out to Hitler’s advantage. He used his trial as a stage for publicly declaring the cause he believed in, namely the overthrow of the Weimar Republic and the establishment of a more pro-German regime. He identified himself as a revolutionary and a patriot, borrowing images straight from the American Revolution.

Instead of ending Hitler’s career, the failed putsch made him a celebrity. National newspapers covered the trial, quoting his words in full. Now he was getting his message out to all Germans, not just the limited following in Munich. Even the trial judges found themselves drawn to this charismatic man. Over twenty-four days, they listened to his rhetoric, stirred by the nationalistic pride he exhibited.

Hitler was not condemned to life in prison – the usual penalty for a guilty verdict in a treason trial. He received a light sentence of only five years in a minimum security prison, with possibility of parole in six months. The court even granted him the privilege of a private secretary, a fellow Nazi named Rudolf Hess.

Over the nine months that Hitler occupied his comfortable cell, he and Hess developed a new strategy for their fledgling party. Hess took dictation as Hitler delineated his social – and racial – policies in a book he called Mein Kampf. He held nothing back. Everything he subsequently accomplished was outlined in that volume in excruciating detail.

In addition, Hitler understood that if he and the National Socialists were to rule Germany, he would have to accomplish the coup by means of lawful usurpation of power. No more putsch attempts in beer halls. They would have to go at this legitimately. And that meant elections.

Once again, circumstances combined to create the best possible climate for National Socialism. October 1929, the same month as the stock market crash known as Black Tuesday, the brilliant German economist Gustav Stresemann died. He had been the brains behind the recovery of the previous years. His death, combined with immediate chaos following Wall Street’s collapse, left the Weimar Republic in shambles. A parliament that already consisted of an unwieldy number of political parties now fragmented further. Splinter parties splintered off into ever more radical circles. The Chancellor, Heinrich Bruening, could not gain a consensus on any legislation, as none of the parties was willing to compromise.

After President Hindenburg refused Bruening’s request to invoke Article 48, a constitutional provision to rule by decree, Bruening called for dissolution of parliament with elections to be held on September 14, 1930. He was also dubbed the “hunger chancellor” because his name was connected to the project to curtail unemployment insurance. Hitler’s time had come.

Hollywood-style productions enveloped the German campaign trail for the first time. While Hitler knew his ultra-nationalistic message would resonate among disaffected German voters, he added a decidedly American component to his methodology: He bedazzled his audiences.

He turned his celebrity status into a marketing tool, campaigning as much on the “spin” that his campaign adviser Josef Goebbels created, as on the cause he believed in. They produced torchlight parades and theatrical appearances, all staged to invoke emotional reactions bordering on hysteria among the masses.

Hitler’s choice of National Socialist flag provided visual clues to his intentions, a clue that was not lost on the people before him. For while the flag of the Weimar Republic sported the colors of the failed democratic revolution of 1848 – emphasis on the word failed – Hitler’s swastika’d flag bore the colors of the old German empire, the empire that had won the Franco-Prussian war of 1870/71.

Political rallies became dramatic events. While we at the beginning of this 21st century are now world-weary participants in teleprompted oratory and tears-on-demand from our presidential candidates, in 1930 Germans were virtual adolescents regarding the abuses of democratic power. They interpreted Hitler’s carefully rehearsed anger, sympathy, and passion as the genuine article, not knowing that behind the scenes, he practiced emoting those sentiments before a camera.

Add stirring martial music (Germans have long been suckers for a good parade), costumed players, gaudy flags, and catchy slogans repeated often to this mix, and you have a recipe for electoral success. Supplement the visual and aural excitement with someone to blame your misery on – Jews – and you are well on your way to being the next Chancellor of Germany.

If all of the above were not enough, Germans indeed had tired of massive unemployment. Nationalists feared that workers could be seduced by Marxists, that bolshevism could sweep across the land and (in their minds) destroy all that was good about the homeland. A politician who could credibly promise to end unemployment, raise the standard of living, and rid them of the Treaty of Versailles without invoking a shred of Communism in the process – that man could buy the hearts of many.

Indeed, in 1930 National Socialists went from being dead last in the political horserace, to the second strongest finish in parliamentary elections. From zero to 107 seats in the Reichstag in one fell swoop!

Having gained political muscle “legitimately,” Hitler set out to expand his sphere of influence. Since continued success depended on social and economic turmoil, brown-shirted Nazis concentrated on upping the intensity of suffering among their own citizenry. Where Hitler had reined in the Sturmabteilung before and given them a respectable image, he now unleashed them on an unsuspecting public. Of course they did not wreak havoc while wearing swastikas. They dressed in civilian clothes before they demolished Jewish homes and businesses.

More important than the terror on the streets, Hitler’s Nazis in Parliament did everything they could to break up whatever coalitions existed within the German government. Over the next two years, as Hitler played yo-yo with the Sturmabteilung (Storm Troopers), sometimes sending them out to seek and destroy, sometimes giving them the face of respectability, he consistently undermined Hindenburg’s authority as President. For him, the ultimate goal was not to hold a cabinet post in someone else’s government. He had set his cap on the Chancellorship. The more that Hindenburg said no to his requests for the appointment, the more determined he became to attain that position.

With Goebbels firmly at the helm, Hitler continued his perilous strategy of divide and conquer. The playing of one conspirator against another became a hallmark of his administration long before he assumed total control. His alliances served purely selfish ends, and as soon as one schemer fulfilled his role in Hitler’s master plan, he would be discarded.

By 1932, National Socialists had sowed such discord in the Reichstag that the country was subjected to four separate elections in one year. In the presidential election of March 13, 1932, Hitler challenged Hindenburg head-on for the German presidency. Neither man won an absolute majority, so a second vote was scheduled for April 10. Hindenburg won, but Hitler had proven that he was a force to be reckoned with. And he had gained a tremendous personal following, with many Germans showering him with the adulation normally reserved for deities. True disciples believed he could do no wrong.

Sensing his ultimate victory, Hitler devoted most of his time during the remainder of 1932 currying favor with industrialists – whom he would need to back the military operations he was preparing – and the military. He had not forgotten that a coup cannot take place without support of the military, nor did he overlook the fact that the cooperation of the revered German army would lend his administration credibility in the eyes of the people.

After Chancellor Bruening was removed from power on May 30, 1932, and elections were called for late July, Hitler’s Storm Troopers rioted across Germany to an extent the country had never seen before. Newspapers reported murders and gang killings, occurrences that shocked the average housewife. It was no longer safe to allow children to play freely on the streets. The very fabric of German life – a life that had been devastated first by hyperinflation in 1923, then by economic depression (1929), and now by massive unemployment – was being shredded before their eyes.

Hitler saw the underlying despair, combined with the artificial distress created by his own hand, as the chance to preach his antisemitic message. The historian Philip Gavin reports that as Storm Troopers roamed the streets, picking fights, they would sing: Blut muβ fliessen, Blut muβ fliessen! Blut muβ fliessen Knuppelhageldick! Haut’se doch zusammen, haut’se doch zusammen! Diese gottverdammte Juden Republik! [Blood must flow, blood must flow! Blood must flow cudgel thick as hail! Let’s smash it up, let’s smash it up! This goddamned Jewish republic!]

I do not believe that I would like to know how that melody goes.

On July 17, 1932, Storm Troopers raided a neighborhood near Hamburg that was known to be home to a large group of Communists. They opened fire, killing nineteen people and wounding nearly 300. Amazingly, local police granted protection to the Nazis.

With so much unrest, Franz von Papen (provisional Chancellor) invoked Article 48 and effectively ruled as dictator. With elections so close, Hitler called out the basic fears of the German populace in his frenzied final attempts to win an absolute majority. While he did not succeed in that goal, on July 31 his party did receive 37% of the vote, rendering it the largest – and most dominant – force in Berlin. Hindenburg could no longer relegate Hitler to an obscure corner of the landscape.

To Hindenburg’s credit, he tried to minimize the damage. Despite Hitler’s dogged demands to be made Chancellor, Hindenburg would not make it so. He offered Hitler the office of Vice Chancellor and Prussian Ministry of the Interior.

National Socialists retaliated by giving Chancellor Papen and his government a vote of no confidence. Before that deed could be concluded, Papen dissolved the Reichstag and called for yet another election. That November vote was to be the fourth time that German citizens were asked to go to the polls in a single year, and it was a bit over the top for the man on the street.

November 6, 1932, National Socialists lost 34 seats but retained their ascendancy. The next two months saw renewed intrigue by Hitler and Goebbels, pitting conspirators against one another. One of those co-conspirators actually gained a short-lived advantage over Hitler. Kurt von Schleicher, former ally of Adolf Hitler, became Chancellor of Germany on December 2, 1932. Hitler never forgave him, and had both Schleicher and his wife murdered in a subsequent purge (1934).

Goebbels’ propaganda machine took care of the momentary crisis. Rumors circulated that Schleicher was going to arrest Hindenburg and declare martial law. Hindenburg found this report believable since Schleicher was a high-ranking army officer. The next day – January 30, 1933 – Hindenburg bestowed on Hitler the mantle of leadership. He sought to minimize Hitler’s authority by making Papen his Vice Chancellor.

Hitler knew that his persistence had paid off. Everything was going according to plan.

If you hadn’t already heard the news the day before, there was no way to miss it this fine Tuesday morning. January 31, 1933, a breath of fresh air swept across Germany. Inge Scholl recalled arriving at the red brick schoolhouse close to the center of town. Dark winter morning, and the sun still had not shown his face. But she remembered the euphoria she felt when she heard that Hitler had been made Chancellor of Germany.

Inge saw Hitler’s ascension to power as something that would bring salvation to Germany. Now she only had to figure out a way to gain access to high-ranking women in the Bund Deutscher Mädel, or the League of German Girls. Their sharp-looking uniforms appealed to her.

Most of all, she reminisced about the dancing in the streets, and all those who shared her joy. It seemed that overnight, things got better.

Fritz Hartnagel’s brother-in-law lived up near the Wilhelmsburg. His blue-shuttered house had been quiet since he had taken his new bride to live there. A budding young architect, he had not had a single project since 1931. Times were hard. He did not know how he could make it.

But within twenty-four hours of Hitler’s becoming Chancellor, he had found work! Nothing insignificant either. He was on his way to success. He thought, this man Hitler, he must be doing something right.

Anyone who expressed qualms about Hitler’s more radical views reassured themselves that Hindenburg was still in control. They pointed to Papen’s appointment as Vice Chancellor as a sign that the old man had not made a mistake. Besides, with four elections the year before, it was clear that if Hitler did not keep his campaign promises, they could vote him out. This was a democracy, after all.

Even the great German-Jewish leader Leo Baeck initially supported Hitler. His newspaper asked the Jewish community to defend the Chancellor. It looked like his proposals would benefit all Germans. No one took Hitler’s more radical statements all that seriously.

Susanne Hirzel was not yet twelve in January 1933. Her world revolved around music lessons, school, and the church her father pastored. About in that order, too. She could care less about the troubles of the Weimar Republic or the ‘miracle’ of Hitler’s becoming Chancellor.

Her most vivid recollection of January 31, 1933? Her oddball Latin teacher, Mr. Ruetz, stood before his class. “Boys”– she was the only girl in the class – “boys, Hitler’s here now. He will bring war, and one of these days, you will see all of Ulm go up in flames.”

Ruetz kept a spittoon in one corner of their classroom. He entertained his students by standing about six feet away, sticking his thumbs in his suspenders, and then spitting. If he hit his mark, he could really get excited.

Only a few days passed after Ruetz warned his class about Hitler. Susanne’s class was told that Mr. Ruetz had “taken early retirement.” And the school removed his spittoon. They told the students that it did not quite fit in with their concept of a people’s community. Ah, the Volk.

But the Hirzel family continued to reserve judgment on the new Chancellor. Ruetz had indeed been a Communist, so the decision couldn’t have been all that bad. Besides, on February 1 Adolf Hitler stood before the German people and solemnly swore that “I will protect Christendom, for it is the basis of our entire morality.” What cleric would not thrill to those words? As long as Hitler stayed true to God, so the reasoning went, Germany would prosper.

Initially, Willi Graf was indifferent to political matters. After all, the Saarland was not part of the Vaterland, at least not yet. He and his friends could hike and pray to their heart’s content, without a thought to the elections that plagued Germans.

But Willi Graf’s indifference to German politics quickly changed. Not because of anything he heard at home. Willi’s father sold wine wholesale. His philosophy of life involved surviving and making a good living for his family. That old Saarbrücken resiliency was plainly evident in the Graf household. Knocked down? Pick yourself up again. People in Saarbrücken had been doing that for centuries.

On Sunday, February 12, 1933, that unconcern changed forever for the blond fifteen-year-old. His best friend Robert joined him after Mass. They read aloud words penned by a dissident Catholic author named Johannes Maassen. “Censorship of the press is as common these days as fresh bread, because German freedom has been sold on the open market.”

Censorship of the press? How could Maassen publish those thoughts if there truly were censorship? They also assumed that Maassen had to be exaggerating when he said that there were 45 million unemployed in America. That sounded like something Hitler would say to prop up his anti-capitalist rhetoric. And Maassen’s claims that one day Catholics would be persecuted just for being Christians, now that had to be utter nonsense. But what if he were right? Willi and Robert could hardly bear the thought.

No matter what they thought of Maassen’s fears, the last paragraph of the document stirred the boys and challenged them, challenged them to be alert, and to be doers.

We seek a national honor that is miles removed from the wretched clay of excess and the gutter. This gutter is fast becoming the norm in daily life and opposes everything that does not worship the current government. We seek the complete existence of justice, the basis of the true State. We seek a gateway for the freedom of the Volk.

Ah, the Volk! Their people, their homeland. And freedom, how badly they wanted freedom.

The Hirzel home, however, remained strongly nationalistic. They may not have discussed Hitler much, but Pastor Hirzel welcomed any leader who would make Germany strong again. Badly wounded twice during World War I, both times Hirzel went back to his troops. In 1918, he had returned to Ulm as commander of his company. He told his children how he had marched down the avenues of Ulm to the cheers of the crowd. He was proud to be known as a patriot.

Susanne had to believe that all was well as Adolf Hitler began his rule. There was a Jewish boy in her brother Peter’s class. Every morning as class got underway, the teacher would ask all the Christian students to rise and recite the Lord’s Prayer, while Heinz Dannhauser remained seated. Then Heinz would stand and recite the Shema while the Christian students sat. Nothing had changed.

But Tuesday, February 28, 1933, whether you lived in Ulm, Saarbrücken, or Berlin, you knew that everything had changed. It wasn’t just the torching of the Reichstag in Berlin. Although that was horror enough! A terrorist attack on one of the most visible icons of German power! Writing this after September 11, 2001, I am sure that Americans finally understand what it means to see a symbol of our country destroyed by people who hate us.

The night before, around 9:30 p.m. a young Dutch Communist named Marinus van der Lubbe was arrested after having set fire to – and destroying – the Reichstag or parliament building. He claimed to have acted alone, but Hitler insisted it was a vast Communist plot designed to overthrow his government. “The Communist revolution has begun,” he proclaimed the morning of February 28.

Two things followed that caused thinking people to worry. First, Hitler had Hindenburg initiate so-called Emergency Measures. These were aimed at weakening the Communist Party. The action caused less of a stir than it should have — after all, seven paragraphs of the Weimar Constitution were stricken — but Hitler could point to similar (short-term) actions taken by his predecessors. And besides, President Hindenburg did sign off on the measures.

Somewhat less noticeable, but equally troubling to jurists was the manner in which he dealt with Lubbe. For he did not have Lubbe tried under existing laws. He created a new law, one which made this sort of arson punishable by death. And then he made it retroactive to Lubbe’s case. German jurisprudence, like American law, had been established on legal norms that date back to the Romans. No civilized country has ever permitted a person to be tried or punished on the basis of a law that did not exist when he committed the crime. But under Hitler, this changed overnight.

A few days later, it became clear that there were not many individuals who had paid close attention to what Hitler had done in the waning days of February. Sunday, March 5, 1933, Germans took to the polls in what was to be their last free election. No hint of that was in the air as they lined up to cast their vote. It occurred to none of them that the press releases issued by Hitler’s newly formed Reich Ministry for Enlightenment of the People and Propaganda, headed by Josef Goebbels, could actually be disseminating disinformation. They gobbled it up and confirmed their desire to have Hitler’s National Socialists run the country.

Although the National Socialists had increased the votes they received by a substantial margin (they had gotten 33.5% of the vote in November 1932, and 43.9% now), it still was not quite enough for an absolute majority. So Hitler formed a final coalition government with another right-wing party, the German Nationals. With that party’s 8%, he had gotten the majority required to take over without further compromise.

Hitler would not be satisfied with a plurality and a coalition government. He wanted it all. So Goebbels set out on an intensive campaign to “align” the nation and the political system.

In the Hirzel household, they had a better idea than most of what exactly was going on. A beloved uncle, Walter Hirzel, was a member of the German National Party, now aligned with Hitler. A Storm Trooper was named Police Commissioner of the State of Württemberg, and prominent Nazis plus Uncle Walter Hirzel filled in the remaining top positions in the state government. Nazis would wait another six months before disbanding the old state forms of government and imposing their “Gau” or regional structure on the country. For now, they were getting Germans used to the idea of incorporating social systems into the National Socialist party. They did not rush to introduce their hierarchy to the country.

If ever there were a time that a citizenry needed to think, this was it. For not even three weeks after Hitler won a plurality at the polls, he and his top agents had managed to align another major segment of the Reichstag. Now they had the 66% vote necessary to destroy the democratic Constitution. Hitler had never intended to rule under German law. He merely used the law to get what he wanted, so he could annihilate it.

On March 24, 1933, Parliament passed the so-called Enabling Act, also called the Law to Redress the Distress of People and Nation. The legislators thought they were passing it for a limited term of four years. But as long as Hitler ruled, the Enabling Act stayed on the books. Only the Social Democrats voted in opposition to Hitler (Communists were not allowed to vote by this time).

Susanne Hirzel points out in her memoirs that even individuals like Theodor Heuss (first President of the new Germany after the war) and Reinhold Maier of Baden-Württemberg – both men considered anti-Nazi by Americans, deemed democratic in their point of view – voted in favor of Hitler’s Enabling Act. They badly underestimated the man.

It is worth noting that the Enabling Act followed an Alien & Sedition Act on March 20 that hardly ever is mentioned in histories about the Third Reich. The March 20 law expanded the definition of treason to include even offhand remarks that were deemed derogatory of Germany or its leaders.

Hitler enticed centrists and Bavarian Catholics to vote in favor of the law by reiterating and strengthening his support for both the Catholic and Lutheran churches. He made these promises openly and in public forum, dripping with enough sincerity that bishops and laity alike believed he must be honest about his plans.

A few people had comprehended Hitler’s long-term strategy, though it was still early in the game. These “wise men” did the things that could have kept Hitler in check; sadly, their numbers were small. Golo Mann reported that the first few weeks of Hitler’s regime, the courts took proper legal action against the atrocities committed by the SS and SA. They released persons who had been falsely imprisoned and reinstated banned newspapers.

Hitler needed the Enabling Act so he could put an end to the good verdicts these judges rendered. And so that he alone could write the laws that governed the land. No checks and balances here. Executive, legislative, and judiciary branches of government were now embodied in a single person: Adolf Hitler.

At precisely the same time as the legislation granting Hitler exclusive right of governance, Heinrich Himmler opened a “prison camp” in a sleepy Munich suburb called Dachau. March 20, 1933, Himmler dedicated the prison at a press conference. Built on a site where a munitions plant had stood till it was abandoned due to the poor economy, the prison at Dachau was supposed to accommodate 5,000 inmates. March 22, the first prisoners arrived, mostly Communists, Social Democrats, and homosexuals.

Theodor Eicke, architect and genius behind what he called concentration camps, modeled the terror-inducing camps after Soviet gulags and British camps established to inter wives and children of male Boers who were fighting for their independence (1898-1901). In the gulags, prisoners intentionally received insufficient food and clothing, yet were farmed out to enterprises in need of cheap labor. Death rate from starvation and exhaustion was high in the gulags, as it was in the British camps for the Boers.

With two good models to work from, Eicke eventually took over the whole system of concentration camps, replicating his success at Dachau. The primary purpose for the concentration camps – in contrast to later extermination camps – was to silence opponents of the regime.

Spurred on by back to back victories, Hitler advanced the next sliver of his agenda: Antisemitism. At the end of March, he decreed a boycott of Jewish stores and businesses. Jews were physically removed from courts, theaters, and hospitals. He met with only partial success. The antisemitism prevalent in the Soviet Union, Poland, and Prague had not yet come full-blown to Germany. By and large, people still liked shopping where they always had, Jewish or not. To enforce the edict, Hitler posted armed Storm Troopers outside Jewish stores to keep people from shopping inside. The boycott was short-lived.

If the boycott was not overwhelmingly popular, neither was it protested by anyone of prominence. To be sure, from now on Leo Baeck and the rest of the German Jewish community were fully aware that the antisemitic planks in Hitler’s platform were genuine. Jewish emigration began in earnest, with scholars and artists like Albert Einstein and Heinrich Mann heading to safer havens. (It also bears noting that while the official boycott only lasted a day, the sentiment regarding not shopping at Jewish stores took root. Things never got better, only worse.)

Susanne Hirzel identifies this as the time of lost opportunity. April 1933, when the Enabling Act had been passed but the ink was not dry, when inflammatory rhetoric to birth antisemitism had not yet gathered steam – this would have been the time for Catholic and Lutheran bishops to stand up in protest, to rally congregations behind justice and freedom. Then and only then, before “moles” lived on every street who reported ‘suspicious’ activities to the government, before parent denounced child and child reported parent, was there enough openness in German society for the clergy to have stood in their pulpits and declare Jew-baiting wrong. Once this window closed, the fight became next to impossible.

But for now, people looked the other way when Jews were arrested on false charges. Hitler was doing what he promised. Unemployment was visibly lower, gangs and murders on the street had all but disappeared (unless of course you were Jewish, Communist, or a Social Democrat). That very real sense of hope, of thinking that tomorrow would in fact be better, saturated daily life. “Made in Germany” once more meant the product was good. Quality and efficiency were once more considered virtues. Once more, people talked of morals, of ideals, of goodness.

Germany, awake!, Storm Troopers had said. Oh, what a beautiful morning!

They could not have imagined that such hard choices would be required of them. They certainly could not have known what was yet to come.

Although this post is free to all, the footnotes and references are available only to paid subscribers. I will also share as a “Note” so non-subscribers can comment.

Excerpts from White Rose History, Volume I, Chapters 3 - 5, © 2002 Denise Elaine Heap. Please contact us for permission to quote.

To order digital version of White Rose History, Volume II, click here. Digital version of White Rose History, Volume I is available here.

Why This Matters is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber. All subscription funds are deposited directly to the account of Center for White Rose Studies, a 501(c )(3) nonprofit. Ask your tax accountant if your subscription is tax deductible.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Why This Matters to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.