The kinder, gentler Hitler, or, the 1936 Berlin Olympics

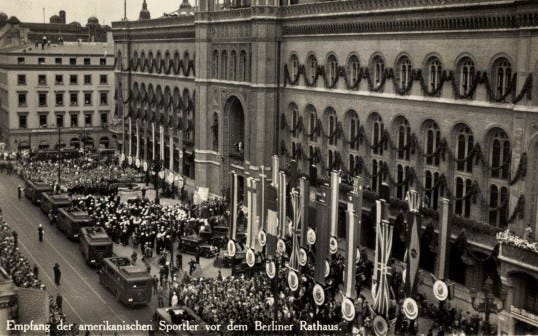

From the moment the pageantry started on August 1, 1936, Hitler endeavored to show the world how progressive Germany had become.

Before Adolf Hitler took radical steps that would isolate Germany from the global community, he ensured that the German people strengthened their ties to one another. His negotiations on the world scene required robust backing on the home front. Additionally, he needed to guarantee that his people would hold together once adversity came. He was therefore willing to take his time repositioning Germany on the international stage, undertaking only low-risk concessions that would not provoke a fight. Germany was not yet healthy enough for all-out war.

The ‘kinder, gentler’ Hitler made his debut at the Summer Olympic Games in Berlin. From the moment the pageantry started on August 1, 1936, Hitler endeavored to show the world how progressive Germany had become. German athletes overachieved during those summer games. The German boxer Max Schmeling reinforced notions of Aryan excellence by becoming the only opponent to win a match from Joe Louis in his prime.

Proud Germans could point to these Olympic games as the most innovative and impressive of the century. For the first time, runners carried a lighted torch from Olympia to the site of the competition.

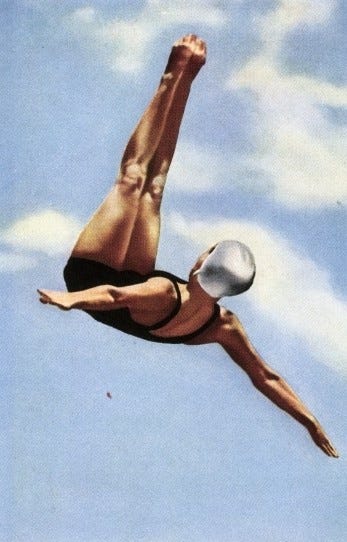

These were also the first Olympics to be broadcast, though television remained a future dream. The NSDAP set up 25 large silver screens throughout Berlin, enabling citizens everywhere to watch the Games for free.

Records were set in Berlin that have not been broken as of 2002. The American Marjorie Gestring became the youngest female athlete to win an individual gold medal (she was 13), and the Danish swimmer Inge Sorensen the youngest medalist ever in an individual event (she was 12, the event was the breaststroke).

Basketball was introduced as an Olympic sport at these games. The Hungarian water polo player Olivier Halassy stirred emotions by winning his third medal, since one of his legs had been amputated below the knee.

And of course, these Olympics established Jesse Owens as a permanent American hero after he won four gold medals in track and field. Despite Hitler’s disdain for “negroes,” Owens’ popularity crossed national borders. A memorable scene, remarkable enough to be included on the official Olympic Web site, involved the German competitor Lutz Long publicly befriending Owens during the long jump.

The Nazis even pre-empted any potential damage that could have come about by exposure of Hitler’s antisemitic policies. They displayed Kurt Singer’s Jewish musicians prominently, validating claims that Germany was treating ‘its Jews’ fairly. Americans visiting surely could not protest Hitler’s assertions that Jews were separate but equal. Not only were Blacks subjected to similar exclusion from society – in many cities, American Jews were likewise second-class citizens. As Kurt Singer’s orchestras played Mendelssohn for select crowds, Hitler convinced the all-important journalists that Germany remained free, with justice for all.

Once the masses left for home clutching medals won on the field of games, Hitler and Mussolini (Hitler’s fellow fascist in Italy) grasped at a chance to have a dry run for eventual hostilities. Franco’s nationalists engulfed Spain in civil war beginning that Olympic summer of 1936. The Germans provided troops – including support from the German Luftwaffe or Air Force – in this conflict.

For the next three years, Germany had the opportunity to test its reborn fledgling military in war games that used real bullets. The rest of the world squabbled about what they should do as battles raged. Some like France came down firmly on the side opposing Franco. Others like Britain and the US chose to stay out of the war.

To the regular German, Hitler was only proving that he delivered on his promises. Germany regained its old position of power – in modern biz-speak, we would say that Hitler became the “go-to” man for European politicians. He was backing a winner in General Franco, demonstrating almost daily that his political perceptions were keen and on target.

Surprisingly, few people inside or outside Germany appear to have made the connection between Germans fighting in Spain and what would follow on the Continent in a few years.

Hitler continued his speeches about Lebensraum, the German need for room to live. Susanne Hirzel recalls a ceremony where women were honored for having large families. The thought briefly crossed her mind that something was wrong with this picture, that if Germany needed more Lebensraum, why would the government be rewarding large families? In hindsight, our vision is 20/20.

In August, military draft – instituted only a year before – was extended by two years. With political sleight of hand, Hitler did not point southwards. Instead, he focused attention on supposed rearmament in the Soviet Union, a fear he knew he could more easily exploit than civil unrest in Spain. The “war games” the Soviets allegedly engaged in could be counted on to unsettle Germans.

Hitler broadened this theme at the Party Day Rally that year in Nuremberg. He assured the assembly, including those who listened to his speeches on Volksempfänger (“inexpensive” government-issue radios costing about $280), that he did not fear a Soviet invasion, “because we are determined to make our nation so strong that she can withstand every attack.” It was unnecessary to prove imminence of such actions. The mere suggestion was enough to mobilize the populace. At least, the parts of the populace that cared enough to be mobilized.

Lilo Ramdohr and her friend Falk Harnack made an excursion to Vienna’s Schloss Belvedere early this autumn. Lilo states that she was a completely apolitical person at this time, not caring one whit who was in power or what policies were in place.

As they drank coffee at the outdoor café, admiring the marvelous view of the countryside their lonely table afforded them, she directed her attentions to the suave young man who accompanied her. It was a slightly dreary late summer day, perfect for lazy discussions of everything unimportant.

The arrival of a long black Mercedes interrupted the reverie. Lilo expressed surprise when Falk got agitated at the event. The fat man and the gorgeous lady who got out of the car meant nothing to her. She could not imagine why Falk reacted as he did. In fact, Falk changed places so that his back was to the moneyed couple.

‘Don’t you know who that is?’ she remembers his asking. Appalled at her ignorance, he explained that the man was Hermann Goering, and the woman the actress Emmy Sonnemann. Ironically, Sonnemann’s name meant more to her than Goering’s, as she had seen the actress’s latest movie.

Many Germans of the day reflected the attitudes that Lilo Ramdohr describes so honestly. Hollywood impacted their lives more than Hitler, or so they thought. As late as Christmas 1937, newspapers highlighted the show times for the same movies that attracted American audiences, films like Shirley Temple’s Poor Little Rich Girl or John Wayne’s The Lawless Range.

German-made movies gained stature in Germany, though even Goebbels himself could not persuade the biggest German star of all to leave Hollywood for Berlin. Marlene Dietrich had signed an exclusive contract with Paramount Pictures in 1930 and churned out one box office success after another for that studio.

Ah, yes, the kinder, gentler Adolf Hitler!

Bonus photographs courtesy of the German propaganda ministry.

Notes and references:

Barcelona, Spain had been Berlin’s main competition for holding these Olympic games.

Marshall Dill notes that despite the official British and French policies, national sympathies were with the Spanish government. Thousands of British and French volunteers went to fight in Spain. Hitler did not contribute many ground troops. “More important, they [the Nazis] also sent units of the new air force, the so-called Condor Legion, which introduced the world to the horrors of mass bombings of civilian populations.”

Texas Rangers played in Ulm on August 7, 1937. The Shirley Temple movie Treffpunkt Paris (with Gary Cooper and Carol Lombard) had been in the theaters on August 2.

All images are from German propaganda ministry, not from the International Olympic Committee. The famous photograph of Jesse Owens and Lutz Long is IOC, and therefore not included here.

Burden, Hamilton. The Nuremberg Party Rallies: 1923-1939. New York: Frederick A. Praeger Publishers, 1967.

Dill, Marshall. Germany: A Modern History. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press, 1961.

Fürst-Ramdohr, Lilo. Freundschaften in der Weiβen Rose. Munich: Verlag Geschichtswerkstatt Neuhausen, 1995.

Hirzel, Susanne. Vom Ja zum Nein: Eine schwäbische Jugend 1933-1945. Tübingen: Klöpfer, Mayer und Co. Verlagsgesellschaft mbH, 1998.

International Olympic Committee/Olympic Games, Berlin 1936: Games of the XI Olympiad. [IOC/Berlin 1936.] Retrieved July 3, 2002 from http://www.olympic.org/uk/games/past.

Jens, Inge (Ed.). At the Heart of the White Rose: Letters and Diaries of Hans and Sophie Scholl. Translation by J. Maxwell Brownjohn. New York: Harper & Row Publishers, Inc., 1987.

Meyer, Michael. “A Musical Façade for the Third Reich,” in Stephanie Barron (Ed.). ‘Degenerate Art’: The Fate of the Avant-Garde in Nazi Germany. Los Angeles: Museum Associates, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1991.

New York Times, September 12, 1936, Party Day Rally.

Ulmer Sturm, August 2 and 7, 1937.

Excerpted from White Rose History, Volume I, chapter 8.

Substack version of this narrative © 2024 Denise Elaine Heap. White Rose History, Volume I, © 2002 Denise Elaine Heap and Exclamation! Publishers. Please contact us for permission to quote. To order digital version of White Rose History, Volume II, click here. Digital version of White Rose History, Volume I is available here.

Not a subscriber?