Women of the White Rose: Traute Lafrenz (part 1)

Reading Traute Lafrenz's Gestapo interrogation transcripts for the first time, I laughed. Out loud. This beautiful young woman stayed a step ahead of her interrogator. How did she become that person?

Last year, I introduced you to Traute Lafrenz’s life - in her own words - from March 1944 through April 1945. We saw how she was betrayed by friends in Hamburg, yet freely admitted to the crimes of which she was accused. And, how she barely escaped death at the hands of the executioner when American soldiers liberated the prison in Bayreuth.

Traute Lafrenz was born in Hamburg on May 3, 1919. Her father Karl held a high position with the Finanzamt, the equivalent of our IRS. Traute would not give much information about her mother Hermine nee Liebscher, nor did Hermine talk much in later interrogations. She’s as good as invisible.

Traute on the other hand was anything but invisible. Her two sisters joined Jungmädel and Bund deutscher Mädel as soon as possible, enthusiastically throwing themselves into Nazi youth activities. Father Karl had missed the deadline for membership application for the NSDAP, but dedicated himself to the NSV (National Socialist Welfare Organization), the League of Expatriates, the German Colonial League, and the National Socialist Agrarian League of Farmers. He additionally was a patron for the NSFK, the National Socialist Flying Corps, a paramilitary organization.

The invisible Hermine joined the National Socialist Women’s League. Traute’s parents waited impatiently for the opportunity to become full-fledged members of the NSDAP.

Meanwhile, Traute joined camping and athletic activities of Jungmädel. In 1933 at 14, she would have been eligible for leadership roles, had she desired. Despite participating in events, she didn’t bother to do the paperwork for membership until 1935. In 1943 when the Gestapo asked her about Jungmädel participation, Traute answered, “I was neither prominent nor excellent in that organization.”

By January 1937, she felt guilty about the appearance of evil. It was not enough to feel uncomfortable at Jungmädel or Bund deutscher Mädel meetings. It was not enough to silently watch in disapproval as bad things happened all around her.

As first small step, she and her friends at Gymnasium copied out and distributed Thomas Mann’s Responsa to the Office of the Dean in Bonn when his honorary doctorate was rescinded. She learned the value of leaflets. Leaflets!

As winter turned to spring that 1937, home life had to have grown more difficult for the almost-18-year-old woman. Two days before her birthday, her father’s membership in the NSDAP became effective. He proudly belonged to the Hamburg-Stadtpark precinct of the Party, member #4230464. His peers noted that Karl Lafrenz was considered above reproach “regarding politics and character” - those peers would not have said the same about daughter Traute.

Although the Lafrenz family considered themselves Lutheran, Traute was drawn to anthroposophy. She defended Thomas Mann. She wasn’t “excellent” at BDM. And now she identified with a banned religion? She was anything but invisible.

Yet Traute volunteered for Reich Labor Service, working six months for farmers. She liked the hard work and the sense of community.

Spring 1939, Traute enrolled as a medical student at the university in Hamburg. Hamburg was among the first universities to convert from semesters to trimesters, with material for a semester crammed into a trimester. Traute found the work at university demanding, harder even than agricultural aid. “It was nearly impossible to do anything outside of class,” she would say in 1943.

That was the official version. In reality, Traute stayed connected to those friends who had published and distributed Mann’s Responsa. They stayed close, Heinz Kucharsky and those others who had been so dear. Sometimes they’d listen to banned foreign broadcasts - together. Moscow. Radio Beromünster. Radio Red Spain. Sometimes they would read banned books - together.

And when someone mentioned a Jewish family they knew and cared about, neighbors in their old quarter of Hamburg, they banded together to help them. [This would later be part of the second indictment against Traute Lafrenz. Apparently she led this operation.]

Traute said their heated political discussions became habit. Even literary soirees turned into political debate, with Traute usually the person who argued against Nazism. The more they thought and talked, the less they found in common with parents who proudly wore Party pins. Hard for these students, who deeply loved parents and siblings, yet had no common ground with them.

The group of dissidents at the university in Hamburg was anything but uniform in their approach to life or politics. Apparently there were three well-organized groups, with overlap and friendship, but different ideas. Traute for example thought the notion of blowing up train bridges was silly, although she remained friends with those more radical friends.

Her mentor was a pediatrician named Rudolf Degkwitz. The group around Degkwitz called themselves Musenkabinett [The Muse’s Room], since they focused on poetry and theater. Degkwitz was a loner, yet he was well-known for having made public anti-Nazi statements and aiding those who were persecuted. He had been arrested and then “rescued” by friends.

The thing that did not happen after one or two trimesters at the university in Hamburg? The paths of Traute Lafrenz and Alexander Schmorell had not crossed, although both were medical students.

But they would meet, and their friendship would be immediate and deep. Medical students had been drafted to bring in the harvest in Eastern Europe that summer of 1939. They did not know that Hitler was planning to invade Poland and that crops in Ostpreuβen [East Prussia] had to be brought in before the fields were cut off by warring factions. Both Traute and Alex were in Pommern or Pomerania, Pomeranian Switzerland to be precise. It’s a region of beautiful lakes surrounded by dense woods. And crops.

One day, these two strangers found themselves sitting on the shore of a lake after long bike rides, each having reached that spot independent of the other. It did not take them long to strike up a conversation. When Alex discovered that Traute liked Russian literature, it was magic. Their first discussion lasted one or two hours.

Traute did not mention Degkwitz or Kucharsky or her friends involved in resistance. They didn’t talk about leaflets. They just talked.

But as they boarded the train back to Hamburg at summer’s end, they spied one another again and waved. They didn’t ride in the same compartment. Neither could know that that summer had birthed a friendship that would change their lives.

Alex soon transferred back to the university in Munich. Traute remained at the university in Hamburg for two full years. Traute’s father moved up in the NSDAP. She became more and more alienated from her family, in her hometown.

Traute briefly studied in Berlin winter semester 1940/1941. Despite common interests, she managed not to meet Käthe Schüddekopf while there.

Once Traute transferred to Munich, things kicked into high gear. She soon met up with Alex, and they restarted the conversation begun two years prior in Pomerania. Alex introduced Traute to his friends and fellow concert-goers, Hans Scholl among them. No one recorded the first conversation when Traute, Alex, and Hans talked politics for the first time. But prior to her arrival in Munich, the young men were content to talk without action, grouse with thinking. Once Traute showed up? Things changed.

She was an uncommon beauty. Traute eschewed the schoolgirl braids and traditional Dirndl the NSDAP promoted as proper for women. Traute wore her hair bobbed short, Pariesienne. She liked high fashion and a polished appearance. She would have been a trophy wife for any highranking Nazi, except for her hatred of that movement.

Traute quickly became a fixture at concerts and literary soirees in Munich. Her friendship with Hans Scholl deepened. They “dated” or accompanied one another to special events. [Hans Scholl never truly “dated” anyone.]

One of Traute’s closest friends from Hamburg visited her in Munich. Ulla Claudias, daughter of the Nazi poet Hermann Claudias and great-great-granddaughter of Matthias Claudias. True to Hans’ nature, he “dated” Ulla at the same time he was “dating” Traute. Rubbing it in her face even.

True to her nature, Traute would not abandon their friendship, despite Hans Scholl’s mistreatment. In those days, having friends with whom she could openly talk about informed dissent and political matters meant more than keeping a supposed boyfriend. She tolerated Hans’ bad behavior, while maintaining the safety net of the friends who still had not become the White Rose.

Occasionally Traute accompanied Hans Scholl - and generally only Hans Scholl - to Prof. Muth’s home, where the two men would discuss high-sounding philosophy. Traute and the other friends were not as taken by Muth’s impractical musings, but there she met Josef Furtmeier, aka The Philosopher. She nicknamed him “the walking encyclopedia,” because of his vast knowledge of many subjects. He was “precise and punctual as the sun,” Traute later said.

As a youth, Furtmeier had championed Communist ideals, espousing the doctrines taught by the Rote Barn, from 1918-1920. As Furtmeier matured, he preferred democracy with a touch of socialism. Traute enjoyed her conversations with Furtmeier. She recalled that he was one of the few Beamte (civil servants) who refused to join the NSDAP and therefore lost his job.

Like Degkwitz, Furtmeier was a bit of a loner who enjoyed a quiet life, the polar opposite of spitfire Traute. He appealed to her because he had “looked at the angle [of] all the Nazi tricks from the very beginning with a clear eye.”

Autumn 1941, things did not improve for Traute on the Scholl front. The very-Nazi Hermann Claudias held literary lectures in Munich. Traute did not attend. She was at home in Hamburg. Traute believed Hans would not attend Hermann Claudias’ lectures, knowing the strong Nazi content that would be presented. Of course, Hans and Ulla were front and center, with Ulla writing Traute a card about the evening.

This aspect of Hans Scholl’s personality - that he felt at home in NSDAP settings and kept up close friendships with people known to be ardent Nazis - bothered Traute and the others in the group. In 1941, when their leaflet operations were not yet underway, it wasn’t quite as bad. But Traute and Alex understood the unnecessary risks Hans took.

The enormity of the risks were highlighted with Ski Trip New Year’s Eve 1941, an event that Inge Scholl has used through the years as her version of ‘turning point’ when they all laughed, skied, and decided to do something significant. Traute’s version of that ski party was censored by Inge.

Inge’s version says there were six participants: Hans, Sophie, Inge, Traute, a girl identified as merely Ulla, and a male identified as Wulfried. In reality, there were seven who left on that journey, with the seventh person being Raimund Samüller. And now we know who Ulla was, and why her presence was a jab in Traute’s eye. Ironically, in Inge’s version of the story, Traute was the girlfriend, though that ship had long sailed.

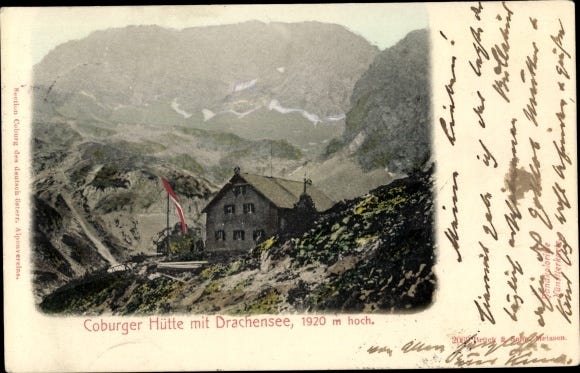

Raimund is left out of Inge’s version because he questioned Hans’ judgment. Their destination: Coburg Cabin, part of the Alpenverein chain of “huts” available for hikers and skiers. Coburger Hütte is in the Mieming mountains, high above Drachensee [Dragon Lake]. In the 21st century, it’s closed from October through May, as it is simply too dangerous to hike (much less ski) those mountains in winter.

Not only had Hans Scholl decided that Coburger Hütte was their destination; he would not change his mind even though it started “snowing a blizzard” halfway up. Raimund headed home. He was not going to be part of Hans’ craziness. Traute continued with the rest of the group, later acknowledging that Raimund was right.

Raimund Samüller never trusted Hans again. He was among the first they considered as the leaflet campaigns started in May 1942. But Raimund flat turned them down. He believed Hans Scholl was trouble.

February through March 1942, without Hans Scholl in tow, Traute spent 3 - 4 weeks with the Scholl family in Ulm. She genuinely liked Inge and Sophie, the two sisters she knew best. Traute especially liked - but did not date - Werner Scholl. She saw him as the only independent thinker in the Scholl family. That’s a solid observation.

One of the funniest Traute stories comes from this time in Ulm. One day, she was at their great apartment by herself. Fritz Hartnagel came to call on Sophie. And found only Traute.

Despite being Captain in the German Army, Fritz was a fairly shy man. Traute was anything but shy. Fritz later wrote Sophie, “Unhappily, the conversation got stuck almost immediately on my sore point, namely my career. How can I make this whole conflict comprehensible to her? First I tried to justify my career, likely out of defiance to her aggression, and then I had to backtrack with concessions. I would rather have crawled into the furthest corner. She certainly must have gotten an odd and confusing impression of me! I believe this is one reason for my timidity with strangers, since there is still so much unresolved within me.”

Once Traute returned to Munich, the group of friends who would shortly call themselves White Rose began to coalesce. Hans and eventually Sophie Scholl. Christoph Probst. Short time later Willi Graf. Raimund Samüller. Hubert Furtwängler. Regine Degkwitz. Josef Furtmeier. Käthe Schüddekopf. And more added every month.

Even the ones like Raimund who avoided Scholl-related events remained a firm part of that circle that found strength and comfort in one another. Traute specifically and emphatically excluded Jürgen Wittenstein. They knew he was a Nazi. His Party pin scared them. But the rest? Oh, how deep the currents of friendship flowed! Those friendships preceded the leaflets by a lot.

Traute had finally found a place she could call home, friends who became family.

Part two — May 1942 - October 1943 — follows next.