April 19, 1943 - The Second White Rose Trial

Subtitle: Women of the White Rose: Traute Lafrenz (part 2E - 4/19/1943).

This “telling” of the events of the trial is presented primarily from Traute Lafrenz’s point of view. The narrative draws on accounts from Gestapo interrogation transcripts, trial transcripts, plus eyewitness accounts. Of the fourteen who appeared before Judge Roland Freisler on April 19, 1943, Susanne Hirzel, Katharina Schüddekopf, Eugen Grimminger, Falk Harnack, and Hans Hirzel recorded their memories of that day in detail. Others like Wolf Jaeger and Traute Lafrenz wrote down high points.

This will be the longest post ever uploaded to WHY THIS MATTERS. It’s an excerpt from Chapter 60 of White Rose History, Volume II. That chapter is more than twiceas long as this post.

On this, the 80th anniversary of the second White Rose trial, please consider the lives – and deaths – of those who faced Freisler that day. May their memories be for a blessing.

The “Green Minna” – police transport – arrived at Neudeck Prison where Traute Lafrenz and seven of her friends had been jailed. The vehicle already contained Susanne Hirzel, Gisela Schertling, and Katharina Schüddekopf, who had been held at Stadelheim. One more stop at the prison on Cornelius Strasse, to pick up Falk Harnack, Willi Graf, and Helmut Bauer.

Despite knowing the Green Minna was headed for the Justizpalast, Traute remained confident that she would not face trial that day. She did not have an attorney. Even in the Nazi justice system, defendants were allowed to have counsel. She decided the prosecution must intend to call her as a witness.

Shortly before the group was led into the courtroom, a nameless person pulled Traute, Käthe, and Gisela aside. They were present as co-defendants.

Another nameless person repeatedly read aloud the names of the fourteen who were to be led into the courtroom. Finally, their “personal guards” (Susanne Hirzel’s irreverent take) readied them for the gauntlet. Police removed handcuffs from the women, but not from the men. Women would be led by the shoulder. Each policeman accompanied his charge as they marched to Courtroom 216 on the third floor of the Palace of Justice.

It all seemed so terribly funny to Susanne. Fourteen “pairs” strolling down a long corridor. She turned to her policeman and quipped, “I feel like I am in a bridal march.” To her disappointment, he acted like he heard nothing and ignored her, staring straight ahead “like a good Bavarian guard.”

Eugen Grimminger failed to see the humor in it. “What kind of utter farce is this,” he exclaimed audibly as the processional began.

Nothing – but absolutely nothing in the world – could have prepared them for the scenes in the hallways and on the stairs of that misnamed Palace of Justice. The sunlight streaming onto their heads would have been enough to grant them strength. All around, every which way they looked, there were crowds and crowds of people.

“Left and right, people were standing shoulder to shoulder,” Falk said. “There were many students from the University of Munich. Workers. Soldiers. We passed them all. Not one person said a discouraging word to us. We received only glances full of sympathy and compassion.”

These friends – some strangers, most bound together by common decency – marched into the courtroom in the prescribed order. Schmorell, Huber, Graf, … Falk Harnack, Gisela, Käthe, Traute. (There’s discrepancy in the order the middle seven entered.) The three women would have seen Falk spot his mother standing by the door. He grabbed her hand and whispered something to her.

Others among that most dangerous fourteen were similarly overjoyed to see loved ones there, supporting them. The Hirzel parents had nabbed a coveted seat inside the courtroom. Susanne’s uncle, Karl Thibault, stood outside the door. As did Mathilde and Martin Luible, Willi Graf’s cousins from Munich-Pasing who knew about his work. Wolf Jaeger, friend to several in the processional, initially had found a seat inside the courtroom, but had been forced out by a Nazi VIP. He too observed and listened from the hallway.

Inside the courtroom, things were less friendly. Falk said it was clear that the atmosphere in the courtroom was “the exact opposite of the conduct we had encountered from the general public in the hallway. The brown Party bigwigs would just as soon have jumped up and beaten us to death.”

The drama of Freisler’s entrance to the court impacted the fourteen defendants. Käthe said that his effect “lay doubtless in the red robe against his face that was not a face, but rather a spookily pale mask, and in his voice that was not a voice, only colorless screaming.” Falk noted “blood-red vestments trimmed in gold.” Wolf Jaeger – standing outside the courtroom – remembered only his voice, which echoed in the corridor as a roar (Gebrüll). Susanne recognized his theatrical approach. “He screamed and gestured, drank a lot of water, treated us like we were the most irksome, dissolute criminals. He especially made a point of insulting Professor Huber. Yet he managed to hold to the technically-correct procedures of a real trial.”

Their names were read aloud, and it was announced that they had been led forth from investigative custody. Then the names of their lawyers: Deisinger for Bollinger, Deppisch for Bauer, Diepold for Graf and Guter, Eble for Hans and Susanne Hirzel and Grimminger, Klein for Müller and Harnack, these were court-appointed counsel.

Deisinger would additionally represent Schmorell as paid counsel. Justizrat Roder had been retained by Huber. This had to have been disconcerting to White Rose friends from Munich, who would have recognized Justizrat Roder as a prominent, influential Nazi attorney.

Moreover, Diepold was now assigned Schertling, Deppisch was assigned Schüddekopf, and Klein was assigned Lafrenz. Someone passed the files for these three women to their respective attorneys.

The trial record noted that every defendant was then permitted to make a statement regarding their persons. None of the eyewitness accounts recorded this privilege.

Judge Roland Freisler himself read the indictment aloud. He did not just read it aloud. It was recited in a “sneering, pathetic manner,” playing to the high-ranking Nazis in the room. Freisler left no doubt in anyone’s mind what the verdicts would be.

A nameless person told Freisler that the indictment just read did not include Traute Lafrenz, Katharina Schüddekopf, or Gisela Schertling. Prosecutor Bischoff never revealed at what point he realized he had left Case 8J 37/43 – the file for those three women – in Berlin. He had next to nothing. He had to have been nervous when Freisler commanded him to deliver an oral indictment against the women.

Bischoff complied, quickly making up charges. (At least he had read the file.) Gisela and Käthe were guilty of preparation for high treason, aiding and abetting the enemy, and demoralizing the armed forces. Traute was guilty of failure to report, plus “miscellaneous criminal offenses.” Wha-at? Criminal offenses? Felonies?

When Bischoff finished, Freisler pointedly told Susanne, Gisela, and Käthe – but not Traute – that their sentence – not indictment, sentence – could be amended to include collusion with the enemy, not merely aiding and abetting, and that they could address this question during the trial if they so chose.

In contrast to the trial on February 22, where Freisler had been all business, intent on in-and-out and quick execution, on April 19 Freisler launched into a very long harangue. It appeared to have been both bootstrapped and well-rehearsed, and it touched on NSDAP talking points.

Freisler talked about “the Scholls, who had already been executed,” describing how they wrote, produced, and distributed leaflets. He alleged that Huber had assisted them in their activities and referred to the defendants before him as “the circle around Huber.” He told of their get-togethers, of the seditious utterances of the group. Much of the language was lifted straight from the February 22 “verdict with reasons.”

Käthe noted that they were all too familiar with the National Socialist catchphrases that Freisler sprinkled liberally throughout this harangue. They had ten years of National Socialist indoctrination behind them.

We knew the turns of speech by heart: “The cell of the individual is not the family, but the State... The State is everything, the individual nothing... Culture and education are subject to the protection and the support of the State. He who opposes this protection in order to go his own way is a traitor of the people and an abettor of the enemy...”

Here, all these turns of speech were rolled into one. They spun off like a schoolbook that had been learned by memory, like a broken record. Whether Freisler himself believed the things he shouted at us? Doubtless he appeared intelligent, at the very least he displayed the flexibility of an actor. Or did he simply want to prove to us his superiority by speaking to us in several different languages?

Freisler followed his speech by reading excerpts from the third, fifth, and sixth leaflets. Susanne said that as he did so, “angry, loud protests rang out in the courtroom. You could see fists raised in anger. I think they would have lynched us on the spot. You could feel the electricity in the air!”

Falk confirmed her opinion. “When the leaflets were read aloud, the hostile excitement in the courtroom grew and assumed a threatening tone.”

If things were bad while Freisler cited the third and fifth leaflets, the words from Kurt Huber’s flyer struck a nerve and poured salt on open wounds. Everyone sitting in that room, from Margarete Hirzel to Eduard Geith to Gauleiter Giesler, knew that Stalingrad had signaled the beginning of the end for Germany’s war effort. No one would privately deny that the war was lost.

But publicly? That was a different matter altogether. Publicly, one spoke of victory, of total war, of Hitler’s brilliant military strategy. Yet Kurt Huber – who now was openly decried as author of these treasonous words – had said, “Our nation stands shaken before the demise of the heroes of Stalingrad. The brilliant strategy of a Lance Corporal from the World War has senselessly and irresponsibly driven three hundred thirty thousand German men to death and destruction. Führer, we thank you!”

And Freisler read those words aloud. He read all of it, every last sentence (Gauleiter Giesler and Chancellor Wüst must have squirmed in their seats as the text revealing their lack of full standing echoed in the courtroom).

Beresina and Stalingrad are going up in flames in the East, and the dead of Stalingrad beseech us: “Courage, my people! The beacons are burning!” Our nation is awakening against the enslavement of Europe by National Socialism, in a new pious revival of freedom and honor!

When Freisler concluded Act One of this command performance, he said that he had been a judge for a very long time, and this was the lowest thing he had ever encountered.

“It was truly grotesque,” said Susanne Hirzel. “Yet though these proceedings were highly dangerous and tenser than you can imagine, I found myself enjoying it all, happy and satisfied. This scoundrel is reading these words aloud to his own shame. Surely everyone in this room has to recognize the truth. That is what I was thinking. What were the listeners thinking, especially the police? Perhaps they knew fear, [thinking] Please don't let it be so.”

Even Freisler could not have predicted the effect that reading Kurt Huber’s leaflet would have on the proceedings. Justizrat Roder sprang to his feet and snapped to attention. “Heil Hitler! Mr. President, Members of the Court,” he began.

He continued, “Since I have just gained knowledge of the content of these leaflets, I see myself as a German and defender of the German nation, as one who is incapable of defending such a monstrous crime. I pray the court to relieve me of my duties as defense counsel and to honor the grounds I have set forth.”

Freisler interrupted his resignation while the gallery held its collective breath. “I will allow you to read the full text during the break.” Justizrat Roder reiterated his position, that he could not possibly defend someone whose offense was so outrageous.

The red-robed judge reminded Roder that he should rephrase his request. “Counsel, you wish to say that your conscience as a Party member will not allow you to defend this man. Otherwise, you would do your duty.”

Then he smiled – what Falk characterized as a “broad, smarmy grin” – and concluded, “Your conduct is most excellent. We have complete understanding for your position and relieve you of your duties as defense counsel.”

Another Heil Hitler, and the “defender of the German Reich” left the courtroom. Freisler designated Dr. Deppisch as Huber’s lawyer for the remainder of the proceedings, and his files were passed along to the only attorney in the room who had bothered to speak with Kurt Huber before the trial started.

Nevertheless, Deppisch publicly protested that he had never seen the file, nor did he know anything about Huber (likely because of the little scene that had just unfolded with Justizrat Roder, and the reaction of the gallery). Freisler was aware that this was not true, since he had read Deppisch’s pre-trial report on behalf of Helmut Bauer and Professor Huber. But he played along with the convenient deception.

“I will read aloud everything that is important,” he said. “You may be certain that I will proceed truthfully.”

Falk Harnack sat next to Kurt Huber and was moved by Huber’s visibly (and deeply) shaken countenance. Huber had not expected Roder – friend and fellow nationalist – to abandon him like that.

Freisler then proceeded, still following “law” by presenting strong cases against each defendant, allowing them to speak in their own defense. And that is how the trial record presented that portion of the trial. But the five who documented their memories of the trial remembered things differently. Susanne wrote:

If the development of a matter was disturbed, or if [Freisler's] tempo was diminished, Freisler would get impatient, scream, and drink water. If a defendant tried to say more than Freisler wanted to hear, he would cut him off, “If you say things I don’t like, I will have you taken away. I will arrive at a verdict with or without you.” He angrily showed his contempt, his condescension, his ridicule, most especially for Alex Schmorell and Professor Huber. He tried to make them look ridiculous and cursed them brutally.

Should one of them slip up and call their mentor Professor Huber? Freisler would launch into another tirade, reminding everyone that Huber had been stripped of his academic title. Mr. Huber! And of course, Alex was that Russian Communist.

When Huber himself stood before Freisler, the fourteen assembled sat up a little straighter. Even those like Falk who had vehemently opposed Huber’s nationalism; or Grimminger, whom Huber had misidentified and denounced; or Alex, who had suffered much under Huber’s harsh pronouncements; or Käthe (and Traute), who had ceased trusting her mentor – even these were awed by the man who now faced Freisler.

The judge reminded Huber – for the benefit of everyone in the courtroom – that the university had rescinded his rank as professor and his PhD, “because he was a seducer of German youth.”

Huber pointed out that his lectures were always filled to overflowing. He had only tried to support German youth with their inner battles, something he considered an integral part of a professor’s duties, especially one who taught philosophy.

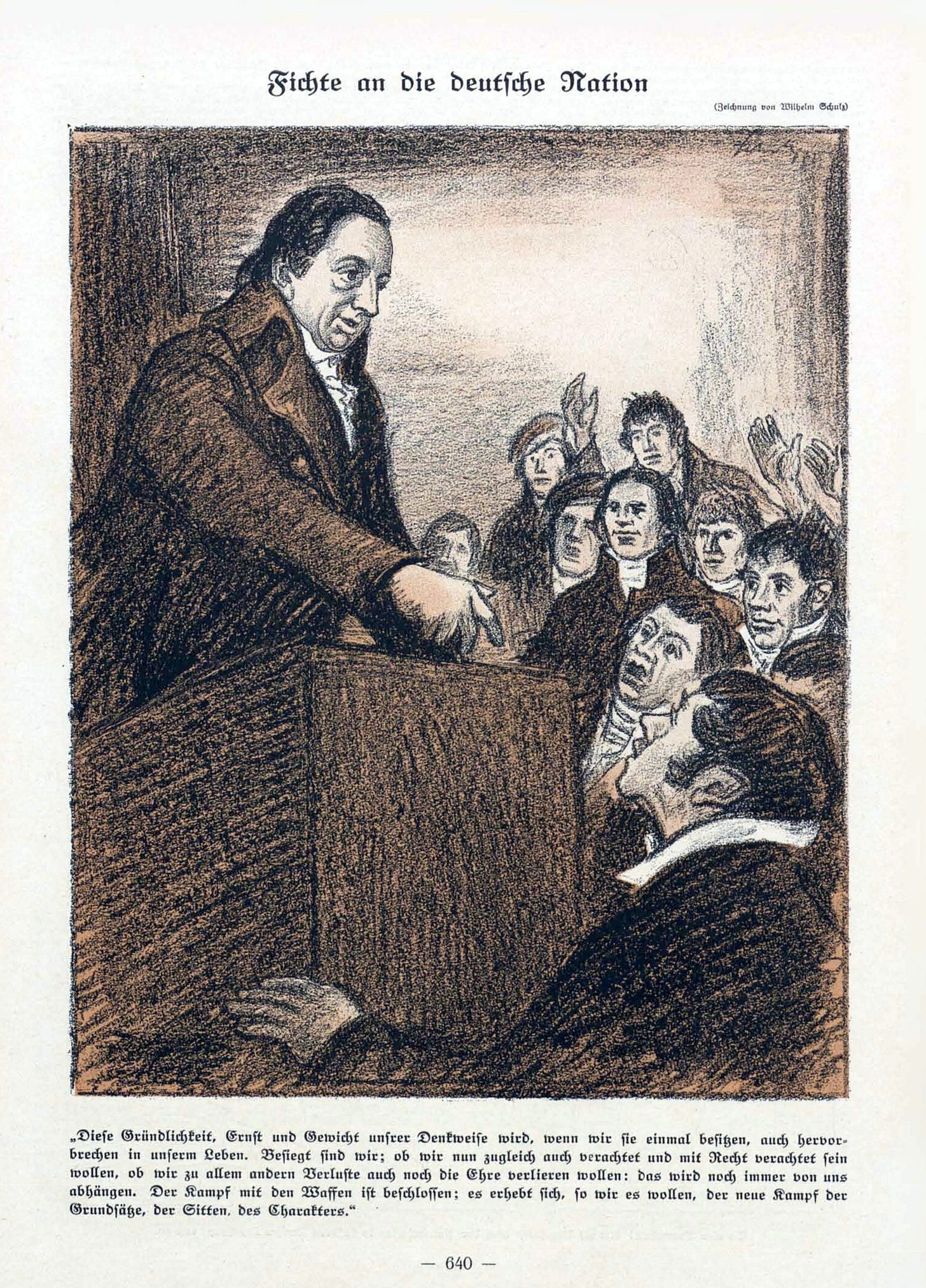

“So, you think you are a modern-day Fichte,” Freisler said. “You write about Fichte. Do you think that Fichte would have been capable of such a base act?”

Without blinking, Huber said, “Yes! Without a doubt! Fichte was a patriot! And a good, old-fashioned German. If Fichte were alive today, like me he would probably be standing before the People’s Court, because he never would have gone along with the things that are happening in Germany today.”1

When Kurt Huber said that, Eugen Grimminger took notice. His lethargy disappeared, that sense of being detached from the proceedings. The stupid things that Huber said and did during his interrogations, that bizarre “he was there” accusation, all was forgotten in his awe for the courage of the man who stood before a very wicked judge. “His life was finished,” Grimminger realized. “He therefore defended himself in accordance [with that realization] before Freisler.”

Falk remembered that this exchange required every bit of Huber’s strength. His physical infirmities were as evident as ever. Just holding himself upright sapped him of needed energy. But that he did, though he shook as he “tried to do battle with this ocean of filth.” There was no fear, no cowardice in Professor Huber’s body, only “deepest agitation and anger at these dishonorable circumstances.”

Freisler mocked the professor. “You’re making it easy for yourself, Huber. Get yourself executed, then your family can collect National Socialist welfare money.”

At one point during the judge’s harangue of Huber, someone handed him (Freisler) a law book. Susanne said he theatrically threw it over the bench onto the floor. “We don’t need law books,” he shrieked. “In this courtroom, the National Socialist heart is presiding!”

Everything after Huber’s testimony was anticlimactic by comparison. Even Tilly Hahn’s defense of her boss Eugen Grimminger, or Falk’s theatrical rhetoric (recorded by his attorney), or the young, weak Hans Hirzel’s newly-discovered backbone – all impressed their co-defendants. But Huber’s words gave them strength.

Traute recalled what happened when she stood before Freisler. All her courage, that cat-like ability to stay one step ahead of her interrogator, vanished in the courtroom. She was inexplicably embarrassed, strangely shy. She could offer no defense for her actions.

Käthe also all but lost her voice. As she faced Freisler, she recalled Agent Geith’s warning, You will be shaved and go home with your head under your arm. That took on a whole new meaning now that she confronted her accuser.

Adhering to legal requirements, Freisler permitted defense counsel to petition for the right to call witnesses. Except for Tilly Hahn, the few witnesses Freisler allowed were ineffective, apparently frightened to testify before that judge, in that place.

Kurt Huber learned that Karl Alexander von Müller – a prominent Nazi intellectual and Huber’s closest friend – also had abandoned him only when Dr. Deppisch announced that that historian regretfully could not testify on behalf of Huber, because von Müller “had to be away from Munich on business.” Falk recalled how deeply that wounded Professor Huber, probably more than any insult Judge Freisler could hurl at him. Instead, Deppisch asked that Gestapo Agent Eduard Geith be allowed to testify that Kurt Huber had always spoken the truth.

Dr. Deisinger did not submit petitions on behalf of Heinrich Bollinger or Alexander Schmorell. Dr. Deppisch did not submit petitions on behalf of Helmut Bauer or Katharina Schüddekopf. Dr. Diepold did not submit petitions on behalf of Willi Graf, Heinrich Guter, or Gisela Schertling. And Dr. Klein did not submit a petition on behalf of Traute Lafrenz.

In defense of the last attorney listed, Traute observed that her attorney did in fact read through her file while Freisler questioned the other defendants, something not noted by either Käthe or Gisela. And he contacted her during the subsequent lunch break, again an effort not repeated by either Deppisch or Diepold. Traute felt a little discomfited, since her file took time away from defendants accused of more serious crimes.

After hearing a few of the witnesses – the remainder declared superfluous, with Freisler himself telling the court what he thought the witnesses would say – Freisler called for a brief recess so the Council could eat lunch. The prisoners were not allowed to return to the holding cell. They sat in their cramped defendants’ box, eating carrots off a tin tray. One policeman kindly brought them a quart of water that was passed among the fourteen friends – and by now, even strangers among the defendants considered themselves “friends.”

Dr. Klein hurriedly told Traute that he did not think her case was all that bad. He did not ask her any questions or find out what she thought of the indictment. There was no defense strategy in his rushed statement, nothing to reassure her that she would not be sentenced to death. In addition, he had given Traute’s meager file to Judge Freisler to study during the recess! (She did not know that he did not have her “real” file.)

After the lunch recess, court reconvened. Freisler read a positive document regarding Gisela Schertling into the record. Then the prosecutor made his requests for verdict and penalty. Most were expected. Death for Schmorell, Graf, Grimminger, and Huber. Penitentiary for Hans Hirzel and Franz Josef Müller – no death sentence, “because we don’t wish to shoot at sparrows with cannons.” Prison for everyone else, with the harshest sentence for… Gisela Schertling! Käthe was next “most dangerous”! Blah blah blah, and finally at the very end, Traute Lafrenz. Traute Lafrenz?!

Traute’s case was substantially aided by Schaefer’s persistent attempts to have her declared one of the primary offenders in the group. Even as she sat in the courtroom that April 19, some of her paperwork floated across Munich and around Germany.

Bureau Number One of Munich’s “Special Court” still anticipated a trial focused on her. On April 19, they followed up the Gestapo’s April 14 message with another one to the People’s Court in Berlin, forwarding a transfer order they had recently received.

There is evidence that some (most?) of the documentation and correspondence was not in the file that Bischoff had brought from Berlin. Of all the paper that had been generated in her case, only the March 15 memo written by Agent Geith bore Dr. Klein’s handwritten note, “File seen, Munich, April 19, 1943.” And then there was the matter of that strange oral indictment for miscellaneous criminal offenses.

Defense counsel, even court-appointed defense counsel, dutifully requested lower sentences for their clients. Klein requested a reduced sentence “in accordance with §84 StGB” for Franz Josef Müller, prison sentence only for Traute Lafrenz, and outright acquittal for Falk Harnack. Klein’s legal defense for Franz Josef Müller indicated that he had not been guilty of participating in White Rose intrigue, merely of continuing to “belong to” a Party that had been outlawed.

Following perfunctory requests for lower sentences by defense counsel, Eble astounded everyone in court by continuing to vigorously defend the Hirzel siblings and Eugen Grimminger. Freisler accepted his request to re-call witnesses on their behalf. Eble himself spoke to the good character of the siblings. Susanne pointed out that Eble was a committed Nazi. But – he did not like to lose in court, especially to Freisler.

After witness Tilly Hahn finished testifying (electrifying everyone gathered), after remaining formalities had been done, Freisler gave the defendants one final statement. He surely expected them to plead for their lives. Instead…

Alex stood before Freisler and calmly confessed that he had carried out the illegal work of which he had been accused. He had done so believing in a better Germany. No apologies. Just a clear admission of guilt.

Willi Graf followed his dear friend Schurik’s example, likewise confessing his guilt, likewise stating he did it because he believed in a better Germany. He expressed regret for his actions, but no one in the courtroom thought for a minute that his “regret” meant he would not do it all over again, given half a chance.

Then it was Professor Huber’s turn. “Huber, I hope I am not going to have to listen to a long tirade,” Judge Freisler said sarcastically as the professor approached the bench bearing his twelve-page speech. To everyone’s shock, Freisler allowed Huber to read the whole homily without interruption.

Susanne was struck by the strong contrast between the “vulgar, screaming judge” and the professor’s glowing countenance. She wondered at the “bitterness and doubt” that tinged his words. What could be behind it? What didn’t she know?

The professor’s students knew some of the back story, though not all of it. They sat enraptured by the man whose classroom they had frequented, the man whose counsel they had sought. Doctoral candidates, medical students, high school boys. Traute, Käthe, Willi, and Alex. Some who had become acquainted with the enigmatic teacher over black tea and champagne, some who were hearing him speak for the first time ever. As one, they sat electrified, energized, rejuvenated. This was better than church.

Wolf Jaeger stood outside the courtroom door, soaking it all in. This was the Kurt Huber he treasured. This was the Kurt Huber who lived a little dangerously, who maybe talked a little too loud with potential Nazi spies in the next room. This was the Kurt Huber who “got” justice and theodicy and funny musical rhymes and tender folk ballads and freedom of speech and separation of church and state and who dandled his baby children on his knee. This Kurt Huber did not speak of the good old days of National Socialism. This Kurt Huber had a clear eye for liberty and justice for all.

Wolf recorded excerpts from this speech, excerpts that are worth quoting in their entirety.

I beg and entreat you in this hour to speak creative justice in the truest sense of the word for these young defendants. Do not allow a dictatorship of power, but rather the clear voice of conscience to be heard, a voice that considers the CHARACTER from which the deed emanated. And this character was likely the most unselfish and idealistic that one can imagine: The striving for absolute justice, purity, and verity in the life of this nation.

My goal was the awakening of the student body not through an organization, but rather through a simple word. Not to any act of force, but rather to moral understanding of the existing egregious damages of our political lives. A return to clear moral principles, to a constitutional state, to mutual trust of man to man, this all is not illegal. Rather it is the restoration of that which is legal.

Within the meaning of Kant's categorical imperative, I asked myself what would happen if this subjective principle (maxim) of my actions were to become law. There is only ONE answer to this question: Order, security, and trust would return to our form of government, to our political life.

Every morally responsible person would raise his voice with us against the menacing sovereignty of naked power over justice, against the menacing sovereignty of mere caprice against the will of that which is morally good. This was that which I wanted to do, that which I had to do.

All external law has a final frontier where it becomes untruthful and immoral, namely when it becomes a pretext for the kind of cowardice that does not trust itself to come against overt infringements of civil rights. A nation that prohibits every expression of free speech and severely punishes every – but every – morally justifiable critique, every suggestion for improvement as “high treason,” breaks an unwritten law that has been alive and well in a healthy national consciousness, indeed that must remain alive.

I personally believe that my exhortation TO CONTEMPLATE the sole lasting basis of a constitutional state is the first priority of this hour. Refusing to listen will bring about the demise of the German spirit and will finally cause the destruction of the German nation.

I have achieved my one goal, namely the presentation of this warning and exhortation before competent judges of the highest station, not simply speaking these words in a small private discussion group. I am giving my life so that I may make this exhortation, this request FOR REPENTANCE [same word as t'shuvah] under oath. I demand the return of freedom for our German people.

No trial for treason can rob me of the inner honor I am due as a university Profess-or, the honor of an open, courageous Confess-or of his ideology and political views. The pitiless march of history will justify my actions and desires. I firmly believe that. I pray to God that the spiritual powers that will justify my actions will be loosed among my people. I have acted in accordance with that voice inside of me.

If the fourteen defendants had not been convinced of the rightness of their actions before this moment, they were dead certain they had done the only thing possible by the time Huber finished speaking. Eugen Grimminger’s admiration for Professor Huber was not even diminished by the fact that Huber unnecessarily and inexplicably repeated in open court his false accusation that he had seen Grimminger in Hans Scholl’s apartment. That question had not been asked by the prosecutor, and it was not clear what purpose Huber’s additional public denunciation served at trial.

Grimminger did not care. “In Huber’s closing statement,” he later said, “there was such an infinite love of the Fatherland and such a love for the German people (Volk), for a people that had been led astray and misled and that was being led to the edge of disaster by National Socialism. In any case, it aroused such an infinite respect in me.”

“Had there been the slightest hope of saving his life before,” Grimminger continued, “it was clear to me that in his defense, Huber signed his own death sentence.”

Huber’s doctoral student picked up on his subtle definition of “Profess-or,” which the uniformed men in the courtroom assuredly missed. “One who takes a stand for something,” Käthe mused. The silence in the gallery – and from Freisler – while Huber spoke had amazed and thrilled her.

On the other hand, Susanne Hirzel truly expected someone in the courtroom to jump up shouting, “Where is justice?” She knew that such an outcry would mean death for the person who said it. But Huber’s speech pointed out how unbearable the situation had become. Surely she was not the only individual there who felt that way. Another witness to the “tragedy in the courtroom” would without doubt come to their defense. Wouldn’t they? – And with this statement, she condemned her own parents, who sat in that courtroom.

Fired up by Huber’s eloquent speech, Eugen Grimminger briefly spoke in his defense. As he approached the bench, Freisler mocked him. “Grimminger, keep it short. You know you could lose your heeeeeeaaaad over this.”

When Susanne Hirzel was asked if she wished to speak on her own behalf, she asked if she could say something in her brother’s defense instead. Freisler noted (for the record) that that was highly unusual. Susanne remembered his “limp, gracious hand movement,” followed by the words, “Oh, we will let her speak.”

Taking her cellmate’s insistent advice, pretty blond Susanne looked Freisler straight in the eyes and said precisely what he wanted to hear, empty, patriotic words utilizing as many empty, patriotic Hitler Youth catch-phrases as she could recall.

Freisler then adjourned the proceedings. The Council “retired to consider the matter,” that is, they left to eat supper and ratify Freisler’s official verdict. This occurred around 8 pm.

For almost three hours, the fourteen friends sat in a holding cell. Someone gave them an awful gray porridge to eat. The four men for whom death sentences had been requested? They were especially quiet, somber.

Professor Huber and Falk Harnack enjoyed a few quiet moments alone in one corner of the cell. Falk harbored no bitterness, no rancor towards the professor for his repeated false denunciations of him (Falk) as “Communist.” After today, he too understood why Hans and Alex revered the man so deeply, despite such deep-rooted ideological differences.

“Isn’t it a comfortless image,” Professor Huber asked Falk, “this so-called highest court in Germany? Isn’t it shameful for the German people?” Susanne Hirzel overheard their words and was stirred by the emotion.

Although the official court transcript stated that the verdict was read and trial ended by 9:45 pm, all witnesses placed events much later – return to courtroom between 10:30 and 11 pm. Freisler narrated the verdict, clearly impromptu, no written document before him. Falk said the reasons given were “epicurean rhetorical verbosity.”

Alexander Schmorell, Kurt Huber, and Wilhelm Graf were sentenced to death, with loss of honor as citizens forever. Eugen Grimminger received ten years in the penitentiary, with ten years loss of honor. Heinrich Bollinger and Helmut Bauer were to be punished with seven years penitentiary, seven years loss of honor. Hans Hirzel and Franz Müller, five years in prison (not penitentiary, no loss of honor). Heinrich Guter, eighteen months in prison.

Freisler found that Gisela Schertling, Katharina Schüddekopf, and Traute Lafrenz were guilty of the same crime as Heinrich Guter, “but since they are girls (Mädchen), they receive one year in prison.” Susanne Hirzel, six months in prison.

All of the above, from Susanne Hirzel to Eugen Grimminger, were to have time served in investigative custody deducted from their sentences.

“Falk Harnack to be sure also had knowledge of treasonous activities and did not report them,” Freisler concluded. “However, his case is subject to such special circumstances that it is impossible to punish him for this omission. He is therefore acquitted.”

Käthe recalled that Freisler added something to the effect of, “This one acquittal is also granted out of thanks for the Führer’s birthday,” a remark that did not find its way onto the pages of the written verdict.

Falk glanced at Alex, Huber, and Willi. They sat still and composed, no tears, erect. Käthe noted that she, Traute, and Gisela were so relieved – it felt like they had been sentenced to only one day in jail. They all knew that the sentences would have been different if they had been tried on February 22 along with Hans, Sophie, and Christl. Not a doubt in their minds.

For one fleeting moment, Susanne hoped that someone would come forward and stab Judge Freisler to death. She even considered doing so. Reason and sanity set in fairly quickly, and she told herself that her very small “fire” would be speedily extinguished if she made the slightest attempt at carrying out such a delicious daydream.

The proceedings ended with the words, “Next trial tomorrow at 9 am.” Clara Geyer stated that the trial for her husband, Josef Söhngen, Manfred Eickemeyer, and Harald Dohrn had been scheduled for April 20, likewise with Freisler presiding. Geyer had been told that he and the other three would receive death sentences.

But not only were Traute’s documents floating around somewhere. So were Gisela Schertling’s. And her testimony was crucial to conviction for the four men on the 20th. Eickemeyer et al was therefore postponed to July 13, and Freisler would not make the trip. Official reason for the postponement: The Führer’s birthday.

Around midnight, fourteen pairs of prisoner-and-police marched out of the courtroom to the police transport outside the Palace of Injustice. Käthe heard the Gestapo agents who had interrogated them grumbling about the light sentences. What was that about the Führer’s birthday, someone protested. But those “common” Bavarian policeman congratulated the prisoners. “One of them hugged me,” Käthe remembered, “tears of joy in his eyes.”

Hans and Susanne Hirzel saw their parents as they left the courtroom. Susanne recalled that she was sorry that her parents had sat through that spectacle. “But I thought it served my father right to have to see by what kind of people we were governed,” she said. “Father, who by nature could not hate anyone, could not fathom the depths of their villainy.”

Ernst and Margarete Hirzel waved to their children, and the siblings said goodbye. It was a poignant moment, one that stayed etched in Susanne’s memory.

Wolf Jaeger waited in the corridor, hoping to catch a glimpse of his friends, people who had done what he would not. They could not speak to one another, but they knew one another so well that the glances he exchanged with Willi and Alex, with Professor Huber, said all that needed to be spoken that night. He followed them out into the darkness of night – blackout! – and watched as they were loaded into the van. He stood there for a while, until the vehicle disappeared from view.

They were to be taken to Stadelheim Prison until Berlin determined which prisons and penitentiaries would hold them for the remainder of the sentence. But all their belongings were at Neudeck and Cornelius Street Prisons. These prisoners did not mind the inconvenience of the two detours. They were in a party mood!

Neudeck Prison was the first stop. Eight – including Traute – disembarked, returning in about fifteen minutes with their “possessions.” Next, Cornelius Street Prison, where Willi, Falk, and Helmut got out and went inside. The prison guards had already collected their things and bundled them up neatly. Falk was impressed that they even had a hot meal waiting for them at that late hour.

“Graf and I were starving,” he said. “We tried to eat, but we could not.” Instead, Willi asked him how it had been with Arvid. Had he waited a long time between trial and execution? They smoked cigarettes and discussed how things had been, how things might be for Willi. “Don’t lose hope,” Falk told him.

A prison guard objected to their smoking in the cell. They stared him down. Willi said to the guard, “That’s quite enough.” The guard backed off and left them in peace. “I hope it won’t be long,” Willi said. “Waiting is miserable.” They talked a while longer before the guard reappeared and told them they had to go, that everyone was waiting.

That bumpy ride through Munich’s cobbled streets, across the Isar to Stadelheim Prison was one gigantic festival. Falk told Grimminger, “In a minimum of two years, the war will be over, and you will be free. These ‘ten years’ mean nothing. The main thing is, you saved your neck.”

Though Alex, Willi, and Professor Huber were a bit more subdued than their friends, even they succumbed to the exuberance inside the Green Minna. Traute said they were all excited and talked very loudly. “Yes, we were even laughing.”

Kurt Huber showed the students pictures of his children. They comforted him with the words, “In ninety-nine days, the war might be over. Who knows?” Evidently, someone in the courtroom had said something that made them believe it could be ninety-nine days before the condemned were executed. Susanne said that Käthe did the best job of distracting her Doktorvater.

Käthe saw the tears that he tried to hide from others. The pictures he showed to the group? Käthe noticed that he had uncharacteristically refused a cigarette someone had offered him. When he wept, he took out those pictures of his family.

For a brief moment, the police transport had been filled with silence out of respect for his sorrow. Alex had moaned “like a wounded animal,” Käthe said. Everyone had paused in their celebration of good fortune, embarrassed by their thoughtlessness. But Willi’s smile returned things to normal, and the party resumed.

The sole policeman in charge of their transport dropped all pretense of law enforcement. “Perhaps he did not quite know what to make of the trial,” Susanne said. He acted towards them like a civilian.

That magnificent and irrepressible joy came to a screeching halt inside the walls of Stadelheim Prison. For the first time, it hit them that for some, this was goodbye forever. “It was horrible,” Traute said. Would they ever see one another again?

Last words, last quick words between friends. Alex was convinced that Marie Luise had betrayed him, but he asked Traute to make sure no one held that against her. Grimminger told Traute that he was disappointed that Hans had exaggerated so much, that the group had accomplished so little.

Then Eugen Grimminger cornered Alex. Why did you confess to so many things, he asked. “Grimminger, if you knew what lay behind me and what they did to me, you would understand.” (And one must wonder about the significance of small details in the interrogation transcripts and post-war memoirs – the table pushed against the wall, Alex’s “red face,” the comment that Russians and Slavs were treated worst of all. Do these things suggest that Alex alone was tortured?)

Grimminger well knew what the Gestapo was capable of. He simply had to recall his panic when Schmauß threatened Jenny’s life in a veiled sort of way. The Stuttgarter obviously believed that Alex had gone through unspeakable things he could only imagine. He forgave him unconditionally.

They followed the guards inside the prison, those final goodbyes filling the air. A “Senior Judicial Officer” waited for them inside. Falk said he “sorted them like goods in a warehouse.” Death sentence to the right, in the corner. Penitentiary to the left, in that corner. Prison, the other side.

“I was left standing alone in the room,” Falk recalled. “You, go over to the corner with the candidates for death sentence, he said.” They were the first to be led away. “Farewell, Lebewohl, fare well,” echoed down the hallway.

Willi Graf’s friend Hermann Krings best summed up the day’s tumultuous events in a 1983 essay.

If the farce of the judicial proceedings before the People’s Court is to have any meaning at all, then it is this: It was not enough to express outrage in leaflets and graffiti and to call for resistance. Outrage must also be recorded in stone specifically and publicly against the instrument of terror that justice had become.

The words of Hans and Sophie Scholl and their friends, the twelve-page manuscript that Kurt Huber wrote in his own defense, the endless interrogations in which Willi Graf had to stand firm despite the specter of death – these are a witness to the other resistance. The documents of these witnesses are documents of another court, in which the defendants have become judges of their pseudo-judges by means of their confession and their [public] opposition.

Today [in 1983], one may call for these sentences and false judgments to be overturned, insofar as they have not been lifted. I will not dispute this. But that will not make anyone really happy.

What is truly necessary: Coming to terms with, and publicly admitting, that justice can become a servant of evil – most surely, when justice allows itself to be represented by a Freisler. But not only then. Also whenever justice allows itself to become an instrument of a dictatorship of evil, even when legally and correctly applied. Then justice partakes of evil, and it must rid itself of such partaking.

This too would be of political significance, just as the powerless witness of the defendants. For a dictatorship of evil distorts [lit. perverts] politics by drawing the necessary institutions of our society into an evil act. These institutions are damaged thereby. This does not apply only to the courts, but also to the military, to science, to those who practice public relations, and to other public institutions.

The moral-political significance of one line of thinking these days holds that our institutions must fully rid themselves of all connection to evil.

If – and only if – the farce of the judicial proceedings before the People’s Court on April 19, 1943 is to have any meaning at all.

If you are curious about supporting documents for any of these Substack posts, check out our White Rose Histories (Volume I, 1/1933-4/30/1942, and Volume 2, 5/1/1942-10/12/1943, along with primary source materials.

Excerpt posted on Why This Matters (Substack), © 2023. Original of Chapter 60 © 2002. Please contact us for permission to quote.

If you would like to read the entire account of the April 19 trial, please contact us and request a free copy of Chapter 60. We will send you a fully footnoted PDF of that chapter from White Rose History, Volume II.

Next post: History of the History of the White Rose – Why so many posts about Traute Lafrenz.

Bibliography for this chapter alone (available only to paid subscribers):

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Why This Matters to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.