Russia via Warsaw - July 1942

Although the soldier students saw little of Warsaw on their way to the Russian front, what they did see impacted their resistance efforts. The White Rose circle would never be the same.

Tisha b’Av. The ninth day of the month of Av on the Hebrew calendar. On that day, the second temple was destroyed. On that day, Jews in Spain were expelled from the country during the Inquisition.

Also on that day – July 23, 1942 on the Gregorian calendar – Adam Czerniakow suicided. Czerniakow had been the head of the twenty-four member Judenrat (Jewish Council) responsible for implementing German orders in the Warsaw Ghetto.

Three days earlier, Czerniakow had worked his way up the chain of command in an attempt to determine whether the rumors he had heard about deportations were true. One after another, Nazi bigwigs had assured him they were nothing but rumors. Mende, Brandt, Commissar Boehm, Hoheman, Deputy Director Scherer: All said they knew nothing about deportations. Scherer even said the reports were nonsense and rubbish [Unsinn und Quatsch] and that Czerniakow could inform the population that there was no reason for fear.

Which Czerniakow did, as he instructed his deputy Lejkin to make it known throughout the area station.

Early the next morning, it became clear that Scherer and the rest had lied. The number of guards on the perimeter of the Ghetto had been increased. At 10 am, Sturmbannführer Hoefle appeared at the offices of the Judenrat. Phone lines were ordered cut, and children were moved out of the garden opposite. Announcement: All Jews regardless of sex and age would be deported to the East – that is, to an extermination camp, although that tidbit was left out – six thousand persons per day.

Hoefle told Czerniakow that for now, his wife was still alive. But the first day Czerniakow missed the quota, she would be shot. Czerniakow pleaded for an exemption for orphans in the Ghetto, but Hoefle denied the request.

Czerniakow was devastated. On July 23, he swallowed a cyanide capsule he had saved for such an occasion. His suicide note read, “I can no longer bear all this. My act will prove to everyone what is the right thing to do.”

As Hans Scholl, Alexander Schmorell, Willi Graf, Hubert Furtwängler, and Raimund Samüller – those five close White Rose friends – sat in their comfortable compartment on July 23, bound for Russia via Warsaw, they had no idea that Czerniakow had died. Nor did anyone but Willi Graf know any more about the Warsaw Ghetto than what Manfred Eickemeyer had told them. They probably did not even anticipate a layover in Warsaw.

This historical coincidence is one of two that links the chronicles of White Rose resistance to the fate of the inhabitants of the Warsaw Ghetto. (The second was the White Rose trial on the same date as the beginning of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, April 19, 1943.) As the soldier students traveled eastward to an unknown destination on the Russian front, six thousand Jews were loaded into cattle cars and shipped to almost-certain death.

But July 23, the Roses simply enjoyed the splendor of the German countryside. Regensburg, the Danube – a bright and sunny day. “It is a beautiful afternoon,” Willi told his diary.

The slow-moving train continued its passage through eastern Germany: Zwickau, Dresden, Görlitz, constantly bearing northeast, skirting the border of Czechoslovakia. Over twenty-four hours for a 350-mile train ride. It was a good thing they were in good company that sunny July 24.

The next day, the train heading for Russia entered Poland. Willi Graf already knew what to expect. This was familiar territory for him, traversed a little over a year ago under conditions far more unpleasant. “Once again, the expanse of the East surrounds me.” Willi would have recognized that they were taking almost the exact route he had covered three months earlier – in reverse.

As the train rolled across the “endless plains of the East,” the friends occasionally stopped their games or “intelligent conversation” to stare out the window. This landscape was unlike anything all but Willi Graf had ever seen. No crowded city streets, no houses built one on top of another. “Trees and sky,” Hans Scholl said. “When the moon rises and bathes the trees and fields in its magical silver glow, you think about Polish prisoners in Germany and understand their love of country.”

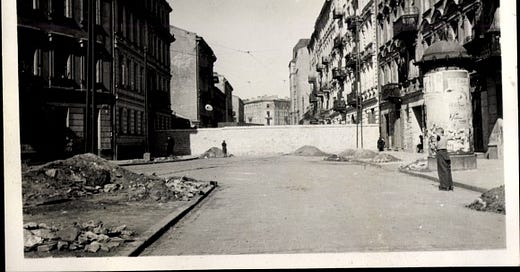

We do not know whether the Roses knew they would stop in Warsaw. But when the train ground to a halt and they learned they had a bit of time to explore this city, they took advantage of the opportunity. It was late afternoon, scorching heat that July 26, a Sunday. “We could not help but see the wretchedness,” Willi Graf recorded in his diary. “We turned away. We slept hard and long.”

After three days on the train – two of them traveling with Italians – the friends were not ready to absorb the gruesome sights of Warsaw. Willi likely would have told them what to expect. On June 12, 1941, he had written Marita Herfeldt, “We have to see much distress here. It is simply everywhere. Especially in Warsaw you stumble across it with every step you take. It is actually unimaginable that it exists. I never would have believed it, never could have imagined it.”

In 1941, the Warsaw Ghetto was plagued with disease brought about by unsanitary living conditions, clearly visible to German soldiers passing through. Only a fence surrounded parts of the Ghetto then, adding to Willi Graf’s nightmares regarding German bestiality and ruthlessness he could not unsee. Over the last year, the fence had been completely replaced with a high brick wall.

That wall may have hidden the worst of the misery, but it did not eradicate it. On this day, the student soldiers could not handle knowing any more. It was almost as if they craved a cocoon to protect them. Manfred Eickemeyer’s tales had been one thing, but up close and personal? This was overload.

Certainly on this day, they did not see the death trains leaving the Ghetto, as those departed from the Umschlagplatz connected to the Ghetto, obscured by 11.5’ brick walls. They would not have seen the death trains leaving Warsaw via the Danziger Train Station; it was three miles north of the main train station where they had halted. They would not have even seen the corpses that littered the streets of the Ghetto, or the long lines of people being herded to the Umschlagplatz, or the unspeakable cruelty visited upon Ghetto residents by German soldiers and their Eastern European cohorts.

The soldier students spent July 27 viewing the horror that was known as Warsaw. Hans Scholl best documented for us precisely what they witnessed:

Warsaw would sicken me in the long run. Thank God we're moving on tomorrow. The ruins alone are food enough for thought, but an American palace towers incongruously into the sky from among shattered walls.

Half-starved children lay in the street and beg for bread while provocative jazz rings out across the way. Peasants kiss the flagstones in churches while the bars seethe with unbridled, callous revelry. The mood is generally one of doom, but nevertheless I believe in the inexhaustible strength of the Polish people. For one thing, they are too proud to succeed in striking up a conversation with them. And children play wherever you look.

And in a later letter to Professor Huber, “The city, the Ghetto, and the whole setup made a profound impression on all of us.” Neither he nor anyone else ever fully disclosed what they had seen of the despair behind the 11.5’ walls.

If these scenes would have sickened Hans Scholl in the long run, how would a full dose of the Warsaw Ghetto have affected him?

The friends took care of more mundane things too while they waited in Warsaw. Willi Graf searched for his friend Sigi, he who also questioned the rightness of becoming an officer in Hitler’s army. Willi was disappointed to learn he had just missed his friend, because Sigi had been transferred shortly before their arrival.

They wrote letters home before they returned to the city, where they walked around, shopped (Willi bought a Russian edition of Dostoevsky’s Raskolnikov [Guilt and Atonement], though it had been published in Leipzig), and ate. They found a restaurant-bar called The Blue Duck, where they “drank vodka in tiny sips.” Before they left the city, they had spent all their money.

Willi said it for all of them, “I hope I will never again see Warsaw under these conditions.”

The soldier students were supposed to catch a 1 am hospital train out of Warsaw heading to Vyaz’ma, where they would be split up. When it arrived, it was filled to overflowing. They had to wait, seeking shelter wherever they could find it. That their “shelter” happened to be the hall in front of the General’s door would have been at once amusing and disconcerting.

Full train or not, they pressed on in the pouring rain: East Prussia, “German Eylau” (Iława), Allenstein (Olsztyn), and Insterburg (Černjahovsk). Willi described these as “great detours” – and he was not wrong. They had backtracked westward, then went due north. Only when the train headed for Insterburg had they resumed an eastbound track.

Willi awoke as they crossed into Lithuania in the dead of night. They had already passed Kaunas (Kovno), east of Königsberg.

The soldier students – now chugging towards Vilnius – were oblivious to everything but their immediate surroundings. Indeed, when they arrived in that border town (Vilnius is the Lithuanian gateway to Belarus), the weather had improved so greatly that Willi stretched out on the grass in the sun. “During these days, one lives in the day. One does not do much. Eat, sleep, read a little, and play chess.” Living in the day meant reading Thornton Wilder’s The Bridge of San Luis Rey in German translation.

When they reboarded, the train traveled north to Dünaburg (Daugavpils), just across the border in Latvia. They evidently spent the night there, because on July 30, Willi said they traveled on shortly before noon, crossing the border into Russia. “The vastness receives us.”

Now in Russia, the soldier students were oblivious to thoughts of home. While they had marveled at the ‘vast expanse of space’ in Poland, they were utterly awed by Russia’s great plains. Even a plague of flies in their train compartment could not ruin the atmosphere. The last two days of July 1942, they spent many hours waiting in cool, damp weather in remote train stations – hours filled with contemplation about where they were and what it meant.

Judging from the diary entries of Willi Graf and Hans Scholl, their conversation centered on two specific topics, if not three. First, the danger represented by Russian partisans (possibly the reason for the delays at Polack) – a danger plainly visible though not seen.

Exceeding that by far, the beauty of the Russian landscape astonished them. Hans Scholl noted that even the desolate railroad embankment glowed with color, as flowers bloomed alongside gutted freight cars, buildings, and distraught human faces.

Finally, these friends acknowledged that as lovely as ‘God’s handiwork’ could be, man had superimposed cruelty, destruction, and despair over the backdrop that so enchanted them. “When will a tempest finally sweep away all these godless people who besmirch your likeness,” Hans wrote in his diary, “who sacrifice the blood of countless innocents to a demon? The whole world is bright again, for as far as the eye can see, after this rain.”

The broad plain may have been a place for these five young men to receive their marching orders and wonder about the uncertain experiences ahead of them. That same plain also awakened a desire in a young person to “go forth, leaving everything behind, and wander aimlessly until he has snapped the last thread that held him captive, until he stands confronting God in the broad plain, naked and alone.”

I wrote the paragraph about what they did not see specifically to set the record straight. Jürgen Wittenstein spun a false tale of their “three days” in Warsaw. To begin with, they had at most 1-1/2 days in the city. The Wittenstein version of events had them (he included himself) seeing things that simply were not visible from outside the wall.

Therefore, our White Rose History: Volume II - Journey to Freedom corrects Wittenstein’s false narrative.

In a move that was at once unnecessary and unwise, the would-be military historian Detlef Bald accepted Wittenstein’s story at face value without historical process to determine whether his words were true. Bald doubled down with a second volume, co-written with a Catholic teacher who would have the White Rose be a Catholic resistance organization, which it was not.

To understand how the Russian front, and the layover in Warsaw, impacted these five young men, it’s crucial to know the true story, not the Wittenstein legend.

For true scholars among our readers, a few questions:

Does anyone know what Hans Scholl could have referred to as “the American palace”? Villanova? Belvedere? Both were prominent palatial structures. Did either have American connections in 1942?

The Blue Duck - intriguing. Any information?

Military historians: Any reason the train carrying the Second Student Company would have diverted from its direct route and headed west?

This Substack post is a summary-excerpt of Chapter 11 of White Rose History, Volume II — Journey to Freedom. Substack post © 2002, 2023. Please contact us for permission to quote. Please note that everything in this post is fully documented and footnoted in WRH2.