Teachers matter

Treat students like adults. Remember when you were twelve and how you wanted to be respected for what you thought and were capable of.

In the Happy anniversary post from July 31, 2023, I mentioned several teachers who impacted White Rose research. We would not be here were it not for those people.

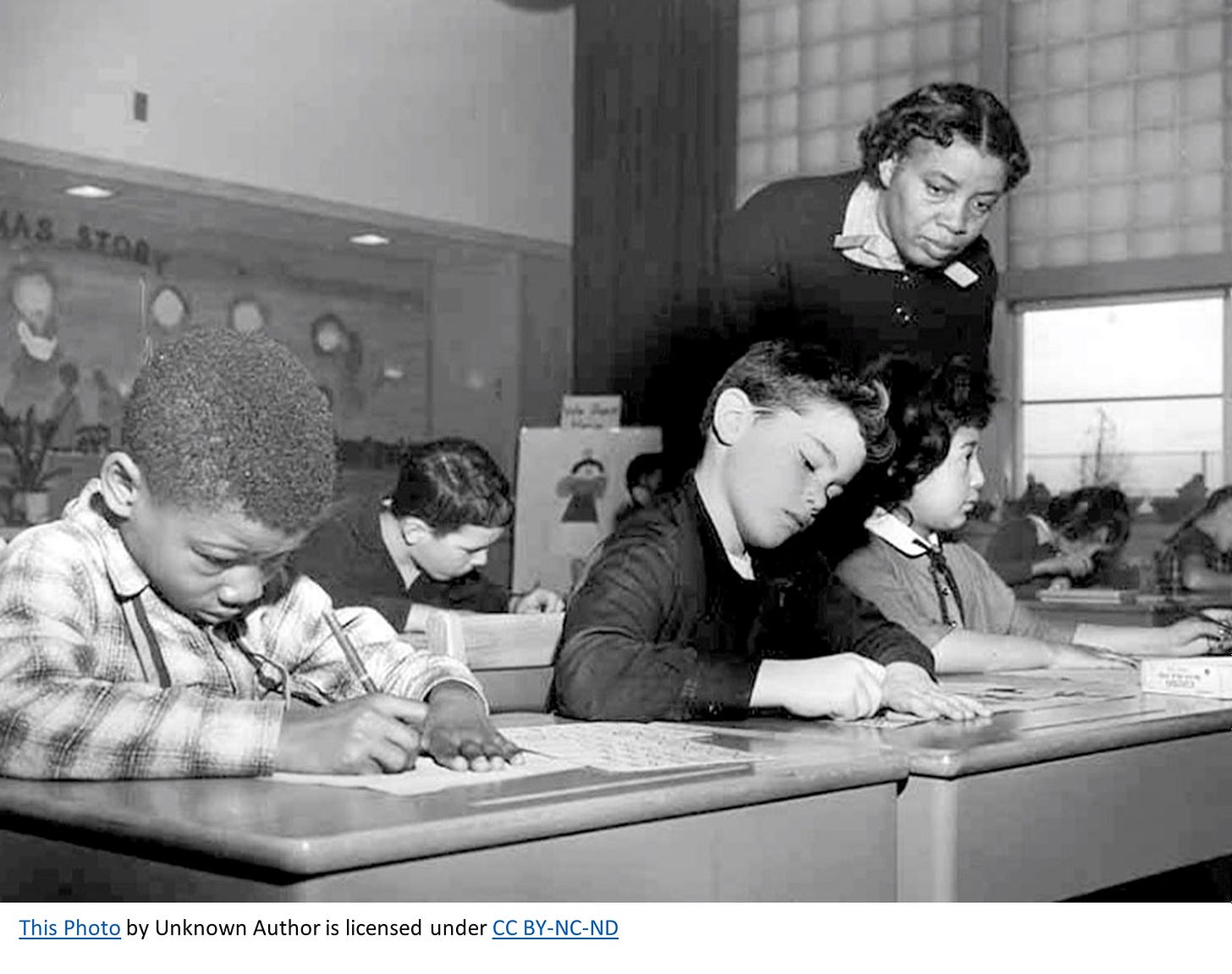

Today, let me zoom out a bit. “Education” is under fire these days. Public school teachers, already overworked and underpaid, are now being asked to serve as counselors, police, child protective services, bodyguards, with fewer resources than ever. The headlines have taken me back to the unbelievably good education I was privileged to receive.

My first five years of school were in an inner-city elementary school. A public school. My father attended the same school as a boy. Several of his teachers were still there, so I had to live down his reputation. He and my mom were invested in our education. Because those teachers knew my dad, his commitment seemed more personal. He helped teachers he admired and respected, whom he had admired and respected for years.

Most of us were first-gen Americans. Our family was different; I was third-gen! So many languages swirled through this small, neglected school. No air conditioning, wrong side of Houston’s tracks. Blue Boy and Pink Girl seemed to stare at us disapprovingly from their vaulted positions in the lobby.

Mrs. Burke was the school’s only kindergarten teacher. Class size was huge, so was the classroom. Looking back, I realize she was probably quietly feeding children who showed up hungry. My mom was her primary co-conspirator, and since my dad worked with Mrs. Burke’s husband, the four of them ensured that our kindergarten class was a fun place, full of things to explore.

She also celebrated the diversity within the class. I think we all tasted one another’s food at one point or another. First authentic Chinese, Greek, Italian, German, Jewish, Mexican, and Polish food was right there in that ragged kindergarten classroom. I traded my mother’s oatmeal cookies for Annie Lim’s homemade fortune cookies. We both thought we got the better end of that deal.

In first grade, I got stern Mrs. B, not to be confused with happy-go-lucky Other Mrs. B, who had taught my dad. My Mrs. B treated us like adults. She posed serious questions, knowing we would not comprehend the entire question, but counting on the fact we would remember the questions. “If half the class is running in the hallway and half the class is not, but the half that is not running is laughing at and clapping for the ones who are running, should everyone’s punishment – standing in the corner, quiet time, note to parents, take your pick – be the same?”

It was also the same Mrs. B who made us memorize Psalm 100 to recite at a PTA meeting. Several parents protested the intrusion of religion on a secular, public school education. I remember that all sides talked calmly. No one screamed at anyone else. At the conclusion, stern Mrs. B admitted that she could see their point, that if someone asked her to recite religious words she disagreed with, she would not like it either. And that was that. Religion stayed out of the classroom and the PTA.

By second grade, Black families had moved into our corner of the school district. They were poor just like the rest of us. No big deal. I think class size started to increase, because the school had to start bringing in temporary buildings (that never left). Everyone wanted to have class in a temp building, because they were air conditioned!

But my second-grade class, taught by gray-haired Mrs. K, was in the main building. She’d open the enormous windows, crack the transoms as wide as possible to get some draft. At one point, the school got us industrial-sized fans that did help, but blew everything off our desks. Comic relief. Poor Mrs. K!

She was the teacher who first lit that flame of learning, who made me want to read every book in the library, ask every question, know everything that could be known. After the report card that said, “Denise cannot sit still and be quiet,” I went with my parents to talk to her directly. Explained, but I am jumping up to go ask you questions!

Mrs. K turned that embarrassing report card into a miracle of sorts. Instead of breaking me, she ‘employed’ me. I got to help her teach! Well, really tutor. If one of my friends did not understand the homework, she would let me explain things to them. I wanted to go to school every single day. When I got the measles – no vaccines then – and had to stay home, I cried. Mrs. K taught me to love school. No, to love learning.

Third grade, I was doubly excited. My classroom would be in an air-conditioned temp building! And I got Mrs. T, the best third-grade teacher in the school. Mrs. T was a middle-aged Czech woman, probably first-gen American, judging from her accent. She understood the struggles her student faced, what it meant not to belong. Parents at home speaking their mother tongue, children trying to learn arithmetic and reading and geography in a language they were still acquiring.

Only a few weeks into third grade, Mrs. T became ill and had to stop teaching. Her replacement was no Mrs. T. Mrs. R had no teaching skills. None. She delighted in humiliating students. My handwriting was atrocious, so she would pin my homework up and mock my cursive. If someone failed an arithmetic or geography quiz, same thing.

Her favorite punishment – for everything – was: Write 100 facts. Luckily, my great-aunt had bought us an encyclopedia, so my frequent fact-writing was easier than it would have been otherwise. Mrs. R inadvertently gave me the love of digging for new, fascinating facts. Not a total waste, I guess.

Redeeming feature for third grade: The school gained a music teacher. Her husband, Howard Webb, had founded the Houston Youth Symphony in 1946. He had a soft spot for inner city kids and ensured we went to dress rehearsals of the Houston Symphony. Several of us joined the HYS – not in its glory days. We met at the old Alley Theater in a back room and made music, and had a great time doing so. But I pity anyone who heard us practicing.

My main memory of third grade: Standing in line at a water fountain under the gaze of Blue Boy and Pink Girl, waiting our turn to enter the lunchroom. There’s an odor of vegetable soup. Pushing and shoving. Our chance to get away from Mrs. R for thirty minutes. And the principal suddenly is talking over the speaker like she did every morning. Only this time, she sounds like she has been crying.

We learned that President Kennedy had been shot. In those days of not-instant news, we knew very little. For the rest of that day, nothing mattered.

When we received word regarding who my fourth-grade teacher would be, I was upset. No one liked Miss Fantz. She had come to our school from a parochial school. She had a reputation for being mean. No one, absolutely no one, wanted to be in Miss Fantz’s class.

It was made worse because a) it was in the main building. In fact, her classroom had no outside windows. And b) because class sizes had grown so much, with budgets shrinking, that instead of hiring a new fifth grade teacher, Miss Fantz had to teach a huge class that was half fourth grade and half fifth. Without an assistant.

It did not take long to bond with her. Yes, she was strict. But Birdina Fantz was anything but mean. She handled that split classroom with grace. In addition to two grade levels in one room, she was responsible for students who were not reading at a fourth-grade level. As Mrs. K had done, she enlisted me as tutor (I swear, we all learn so much more when we teach!).

Miss Fantz also had apparently become friends with Mr. and Mrs. Webb. Music became a larger part of our curriculum, thanks to the Webbs who seemed to live at our school. Mr. Webb moved rehearsals from the old Alley Theater to Macarthur Park, so children without transportation could participate.

Partway through that year, Mr. Webb handed the HYS off to Robert Linder, an unknown at the time. Mr. Linder treated us like adults, although I feel certain we drove him nuts. We learned music composition from him, and he played and critiqued our little songs. Little songs perhaps, but oh! How important his recognition of our work made us feel! [He taught us that we should never write a song to be sung that included a full-octave jump in the score. He demonstrated why that made the song difficult to perform, making us try it for ourselves. Years later, I wrote a piece specifically for a fellow who’s a first-class tenor. And the first two notes are a greater-than-an-octave jump. He pulled it off!]

In fifth grade, we moved to Houston’s suburbs. We had been renting from my paternal grandmother, and my mother felt it was high time she and my dad had a home not quite so close to (his) family. How disappointing that fifth grade class was for me! So white bread. Do you know how boring it is to sit in a classroom where there’s no first-gen accents, and no homemade baklava at George’s birthday party? And no mangia mangia!, when you lucked into an invitation to the P’s house? Where the parents let you sneak a little wine?

Fifth grade is a blur, teachers being circumspect. I made friends for life there (as I had at the earlier school), but the teachers were not memorable. Same in sixth grade.

Seventh grade was another turning point, with Marie Louise Pieratt nee von Gronau, that German teacher whose father had been in the resistance, mentioned in the Happy anniversary post. Add in an English (grammar) teacher who showed us slides of her trip to Europe – many of us were bit with the travel bug after that! – and who taught us to take care who our friends were, and what we put into our minds. “You are who you have been becoming,” she would say, many times during the year she would say that.

And the seventh-grade social studies teacher, Kent Skipper. Like Robert Linder, Mister Skipper was an unknown in 1967. This was before he was Dr. Skipper, acclaimed Dallas educator.

Mister Skipper dedicated Wednesdays to off-book teaching. What do we dream about? Have you thought about what you want to be when you are your parents’ age? Your grandparents’ age? Once he tricked us. “What do your parents do that makes you mad?” We had no trouble with that topic. For one full hour, we unloaded.

The next Wednesday, “So, how many of you have talked to your parents about what we talked about last Wednesday?” One lone student had done so. Mr. Skipper: “So, how did they take it?” – Barry: “It went all right, I guess. It was actually a nice conversation!” That segued into Mr. Skipper’s asking, “When you are parents, what could your kids do that you would absolutely forbid?” – Interestingly, no problem answering that question either.

The bombshell. “How are the things you would forbid for your children different from what your parents forbid for you?” Following a long silence, which Mr. Skipper did not interrupt, the discussion took a serious turn. Just as the bell to change classes was about to ring, the bigger bombshell. “When you are old, remember today. Remember what it is like to be twelve. Remember how you want to be taken seriously. And take twelve-year-olds seriously. When you are old.”

Mr. Skipper also taught us that grief is stronger than anger. Someone in our class – he never said who – had cheated on an exam. When he learned about this, the next day he pulled his stool to the middle of the room, sat down. And cried. Real tears. He then told us that he had learned someone had cheated, and this hurt him. “If you ever lose trust…” I don’t think he said another word the rest of the class. We sat in silence, watching him grieve. Powerful lesson.

These are the highlights of K-7. Highlights only. In high school, my luck continued. Teachers who treated us like adults, who kept those embers stirred and fanned flames of passion for learning.

As that seventh-grade English teacher taught us, we are who we have been becoming. The friends chosen then? Most are still in my life, in one another’s lives. I am beyond grateful for everyone who knows the Denise with rough edges and keeps on loving. I am beyond grateful for teachers who saw tiny little sparks of something and encouraged me to pursue, pursue, pursue, who wrote letters of recommendation, stayed after school to teach some more, who let the Math club organize intramural sports and an after school tutoring program, who chaperoned our trips to TAGS conventions and directed German Club plays – Biedermann und die Brandstifter!, Der Froschkönig! – who turned us loose on a “book report” that became a full-fledged production of Our Town. After all, why not? Indeed, why not?

And parents good, bad, indifferent, but who went along with crazy ideas. Who didn’t worry when we stayed out past midnight at the Galleria watching “Not-Mrs.-Evers” ice-skating, or who shut the bedroom door when we played canasta all night and didn’t mind the yelling of “don’t let John pick up the pall!” [IYKYK], or who always made sure there was Blue Bell Homemade Vanilla Ice Cream in the freezer and root beer in the fridge, just in case friends dropped by to watch Planet of the Apes. (My mom: “It’s more fun watching you all watching TV than it is to watch TV.”)

This is absolutely, 100%, positively not a post, longing for the good old days. There were no good old days. One of those high school friends whom I adored, because she made me feel like I was one of the cool kids when I wasn’t, that cool kid jumped off a bridge in college. How could Jillie do that? She had everything to live for. Others quietly lived through sexual or emotional abuse, trauma no kid should have to deal with. Drug and alcohol addiction was not uncommon. My own sister could not conquer her demons and suicided when she was twenty. Smart, funny, talented, beautiful, and unknown to anyone, insecure.

So no. No good old days rant from me. Life is hard, no matter what “Gen” you belong to.

But education is one of those tools that can help us navigate our questions. I spent so much time on the K-4 part of this post, because it was a poor school with limited resources (but a well-stocked library), and dedicated teachers. Yes, money does help, but it is not necessary for a good education, for teachers to teach well.

And yet, it remains a privilege for people like me who luck into a long string of teachers who find it within themselves to work past the limitations to keep on lighting fire after fire in the bellies of their students.

As limited as resources were for these teachers, at least they were not handcuffed by administrators, governors, and what-all. They did not live in fear of being fired, they were not expected to get concealed weapons permits, they didn’t have to check backpacks for pistols. Although Poe Elementary in Houston experienced a school bombing on September 15, 1959, with five dead plus the bomber, we as students did not worry about a repeat.

My public school teachers got no grief when they showed us naked David, or when they let us gripe about our parents, or when they threw out the day’s curriculum and let us head down to the auditorium to “do” Our Town.

When I was in my forties, my mom told me background to some of these situations. For example, it was a problem for some of the parents when Black families moved into our area in second grade. Every May 1, we danced around a Maypole. It was a big deal. The problem for the racists in the school? They worried that if “white” students held hands with Black students, that Black skin would rub off on white kids. See, people have always been stupid.

The principal, bless her heart, defused the situation and the Maypole tradition continued. With “white” kids holding hands with Black kids holding hands with first-gen Chinese, Jewish, Italian and what-all kids. And everyone was still their own ornery selves afterwards. There probably would have been a bigger earthquake if someone had revealed that May 1 was a “socialist” holiday, because Texas was loath to let go of the McCarthy era.

All fine and good, I can hear you say. But what does this have to do with White Rose, with German resistance, with genocide, with…

When White Rose is taught, I don’t want it to be sugary sweet and sappy. With all that is in me, I beg you, please avoid Inge Scholl’s book if you’re teaching White Rose to middle school, high school, college kids. They are way smarter than you think they are.

I’m not just talking about Hans Scholl’s homosexuality, pedophilia, and drug use. Nor about Christoph Probst’s clinical depression. Nor about Sophie’s suicidal ideation. Nor about Willi Graf’s nightmares. Nor about the fringe people who were too frightened to actively participate, even though they agreed with the leaflets.

Yes, all those things are important. But there are bigger questions that your students need to hear, need to hash out with you guiding them, guiding, not cramming down their throats.

Is assassination moral when there’s someone as evil as Hitler in power? If no, why not? If yes, who gets to decide when someone is evil enough to assassinate?

If there is a cause that you firmly believe in, that addresses an injustice that is so great you cannot keep silent, but participating in protests means alliance with people who hold values diametrically opposed to yours, what takes precedence? Case in point: During the second and third Bush wars, there were large and loud anti-war protest marches. Both Jewish groups and Nation of Islam groups organized to march and learned that the other group would be there. For some Jewish and for some Nation of Islam individuals, they would not join the march because of the presence of the other. Other case in point: White Rose fell apart once they realized they represented Communist, democratic, federalist, monarchist, and other political viewpoints. They would not work together.

What is the definition of a good [your religion here]? Going to church, mosque, shul? Studying Torah, Quran, the Bible? Serving mankind? What is the difference between spirituality, faith, and religion? If in a German class, between fromm and gläubig? What do those things look like?

This may sound silly, but it’s real. What is the best way to commemorate places where genocide occurred? What happens if a well-meaning memorial leaves out a group that was murdered at a site? In Germany, this is aktuell, because many memorials focus solely on Jewish victims of the Shoah and leave out Roma-Sinti, Jehovah’s Witness, homosexuals, Socialists, Communists. Even many that include Roma-Sinti, Jehovah’s Witness, and homosexuals refuse to include Socialists and Communists. And in former East Germany, it can be opposite. And in Eastern Europe, the focus sometimes seems to be on “anyone but Jews.” How do you deal with this? Note: Follow Kriegs-Enkel Stuttgart on Facebook for more on this topic. They do not spare feelings. Nor should you, if you are a teacher or professor.

Turn your students loose on concrete examples of Holocaust revisionism. Get them to talk about Holocaust denial. Make it real by bringing it forward to current genocides. In 1979, the Mother Superior of the Carmelite Convent at Dachau fought with her Catholic overseers. She firmly believed that Dachau should add a section about ongoing genocide and they did not like her suggestion. She did anyway. I admire that woman more than she will ever know. Guests who entered the convent got a full dose of reality. Ask your students: How can we document genocides – historical and current – so they are undeniable?

Get non-history, non-German, non-Holocaust Studies students involved. Music! Food! Databases! Literature! Science! Math! Art! Everything affects everything. Encourage them to link the things they are most interested in with the subject you are teaching. Let them teach you.

Above all, treat your students like adults. They are much wiser than you give them credit for being. They can handle nude statues without becoming addicted to porn. (If Anne Frank could see those nude statues as a young teenager, they sure can.) They do not require nearly as much shielding as you think they do. Except for shielding from sexual and emotional abuse at home. And in churches. We’ve got to get a handle on that. But shielding from ideas? Nah. By the time they are twelve, believe me, they can handle just about anything you throw at them.

It starts in kindergarten, if not before.

Teachers matter. Your kids, our kids, matter. We are their village, like it or not. Make your time count. It’s shorter than you think.

We are who we have been becoming.

© 2023 Denise Heap. Please contact us for permission to quote, or with questions.

I had to ‘blur’ the names of teachers who may or may not show up as answers for security questions. I wish we’d get a handle on cyber crimes! One day…

Did you have teachers who changed your life? If so, what did they do? What do you remember from elementary school that you still use as an adult? What reservations would you have for teaching White Rose and German resistance in unvarnished fashion? Drop a note in the comments below!